Two weeks before he was assassinated in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. called organizer and activist Walter Palmer to discuss some concerns Black youth in Philadelphia had about King’s commitment to the anti-war movement. The youth asked Palmer to speak with King and let him know of their grievances.

Palmer was supposed to be in the Audubon Ballroom on the night Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. He had planned to catch a train to New York City, but fell asleep while babysitting his niece. When he awoke, he turned on the television and learned that Malcolm X had been killed.

Born in segregated Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1934, Palmer moved to segregated Philadelphia at age 7 and grew up in an area known as the Black Bottom—32nd Street to 40th Street and University Avenue to Lancaster Ave.

He was arrested multiple times as a teenager and was in and out of juvenile detention facilities from ages 12 to 17, before turning his life around and becoming an accomplished and respected medical professional, educator, activist, and lawyer, and one of the most sought-after grassroots organizers in the country.

A major force in the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power Movement, Black Liberation Movement, and school choice movement, for decades Palmer was the go-to person locally and nationally for individuals and groups interested in organizing around a particular issue.

He was also actively involved in organizing the political campaigns of a host of the Black elected officials in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, including former Pennsylvania State Rep. David Richardson, former Philadelphia City Councilman John F. White, Jr., and current Philadelphia City Councilman Curtis Jones, Jr., and he ran the Philadelphia presidential campaigns of Teddy Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, and Jesse Jackson.

Palmer’s relationship with Penn began in the early 1950s. After graduating from West Philadelphia High School, he worked as a surgical attendant at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. At the insistence of his supervisor, Virginia Deckman, he enrolled in the School of Medicine’s Oxygen and Respiratory Therapy Program.

He began lecturing at Penn in the early 1960s and has been an adjunct professor in the School of Social Policy & Practice (SP2) for 30 years. On Thursday, May 13, from noon to 1 p.m., Palmer and Ben Jealous, a visiting scholar at the Annenberg School for Communication and former president and CEO of the NAACP, will discuss “Evolving Equity and Education” for the SP2 Speaker Series. The virtual event is being hosted in conjunction with the Office of Social Equity and Community.

Approaching his ninth decade, Palmer, 87, is in the midst of a nationwide campaign to gather 1 million signatures before the end of the year to demand that the U.S. government declare racism in America a national public health crisis.

“My life has seen a lot of ups and downs, and a lot of twists and turns over the years, but I never bowed, I never recounted, I never lost my steps,” Palmer says. “I never backed down.”

Penn Today spoke with Palmer his six decades of activism, growing up in the Black Bottom, studying and teaching at Penn, his work at CHOP, the student strike of 1967, the Vietnam War, Frank Rizzo, Donald Trump, school choice, gun violence, the Chauvin trial, and why he thinks racism should be declared a national public health crisis.

You have dedicated your entire adult life to activism, social justice, and equality, first for Black people and now for all people. Where do you think your commitment to these issues comes from?

There were a lot of challenges in my life and I had to fulfill a lot of different roles, and I think those things nurtured me into being the activist that I became for the next 65 years. I experienced separation of family early in life. I experienced racial separation and racial segregation, racial discrimination, early in life. I saw and experienced male dominance over females. I saw a father who was very strong, a mother who was very strong, and I had a moral compass from my great-grandmother and grandparents. We were rooted in the Black Church and, later on, the Catholic Church to help the family.

How did you experience racial segregation?

Blacks had been coming to Atlantic City since before the Civil War. As their numbers grew, they were sequestered toward the north side. The dividing line was Atlantic Avenue and Blacks were sequestered toward the north; that was going toward the bay. White people, for the most part, were flocking to the south side, which was toward the ocean. So, like most Black folks, where Blacks lived in Atlantic City was predetermined; they were ghettoized to one side of the city. Blacks would help to build the boardwalk but were not welcome to walk on it. They would help to build the hotels, but could not get a room. They would help to build the schools, and the schools were segregated. They would help to build the restaurants, but could not eat in them. The hospitals were segregated. The beach was segregated.

When I moved to Philadelphia at age 7, I lived in a community that was segregated. White people lived to the south and Black people lived to the north. Market Street was the dividing line. So all my life I have had to negotiate between racial segregation and prejudice, notwithstanding the fact that I was confused as to why this was.

Early on, I learned to recognize the fact that it was an accepted practice, no matter where you went. I became more curious in terms of reading, and watching, and listening on the radio, and later on TV. I fought hard to try to educate myself; I tried hard to educate my siblings; I tried hard to educate my friends. The kind of things I was trying to educate them about were these questions about difference and the way in which we were treated because of our color, and how important race was, and how emotionally invested people are in race. It was the beginning; it was the early development.

How did you experience family separation?

My grandmother—my mother’s mother—had 10 children. My mother would go on to have 13 children. The 13th child died two weeks after birth. I was the second oldest. I had a sister who was older. My family was too large for the two-story home we lived in, so my five sisters had to be parceled out to aunts and great aunts between Atlantic City and Philadelphia. When we moved to the Black Bottom, my stepsister let my father live in the back of her beauty shop, so he had two rooms behind a beauty shop. He brought me, my mom, and my two brothers to Philadelphia, and the five of us lived in these two rooms.

But my father wanted to get his children back; he wanted to bring all of his children back together. But he died before he was able to bring the family together. I then became parentified at 12 years old. I had to be the man of the house. I had to help my mother bring our family back together. I had to go out and find work, and that’s what I did.

Why did your father move your family from Atlantic City to Philadelphia?

My father couldn’t get much work in Atlantic City. Atlantic City was seasonal so everybody who lived there had menial jobs during the season. But in the wintertime, the place shut down, so you would go on welfare or public assistance, and you had to figure out ways to make an income. My father worked at the farmer’s market. He was paid very little money, but he was given groceries—meat, fish, and produce—so he could feed his family. He delivered coal or wood or ice or clams, anything to make money. He would take me and sometimes my other brothers and sisters to the beach at 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning when the tide came in to comb the beach to try to gather anything that was swept up on the beach. Sometimes sailors would lose their wallets or people walking on the beach would drop money. We didn’t have a Geiger counter so we had to shovel and sift through sand. He would push rolling chairs with white folks in them down the boardwalk. Black people had to find a way anyway they could.

What sorts of jobs did you do when you became parentified at age 12?

I did all kinds of work. I went out junking and selling junk, before, during, and after [World War II]. There was a premium for collecting papers, iron, rags, glass—you could sell all that stuff. I did migrant farming at 14 years old. I’d get up in the early morning and go off in these trucks with these grown men and women and pick various kinds of fruits and vegetables all day long in the hot sun—and still have to go to school. I was a musician. I learned how to sing and dance and play drums. I was a good jazz tap dancer and a good Afro drummer, and I had a good voice, so I would perform on the corners in Center City and take the money home to my mother. I had my father’s work ethic. I did anything and everything to help protect my mother and my family.

That also drove me to take care of other people’s children. I became protective of the neighborhood. I admired the older guys in the community who were protective of the community and I wanted to be just like them. I couldn’t wait to take on that responsibility, so by the time I was 15, 16 years old, I became a warlord in the community, a protector of the neighborhood, a decision maker. It was a very powerful position in every community.

What is a warlord?

It’s a position. It’s a rank in the community. You become a warlord when you get to the point where people look up to you, people follow you, and people are committed to you, and they have confidence in you and take your advice and your direction. I would go through the neighborhood, just like the older guys used to do, and make sure the young kids were protected, make sure the young girls were not be bothered while they were playing jump rope, hopscotch, jack and ball, Double Dutch. And they knew that there was somebody who cared about them. They knew that the group I was with had to care about them too because I made sure that they cared the same way I cared. We would protect the elderly and make sure people were courteous to the elderly. Warlords were a moral compass.

You spent a large part of your teenage years in juvenile detention facilities. Was there something that caused you to change your ways?

No, there was no epiphany that took place. I always knew the difference between right and wrong. I think what happened is youth is wasted on young people many times, and I think those were instances when it was wasted on me.

You mentioned that you looked up to the older guys in your neighborhood; who were some of the people that influenced you in your youth?

My great-grandmother, who was a former slave. My grandfather, who the caretaker of the house. My grandmother and my aunts and uncles. My father was one of the great influences in my life. He was a strong little guy, courageous little guy. He had unbounded love for his children, his family, his wife.

Before I left Atlantic City, I fell in love with Paul Robeson, watching some of his great movies and being influenced my him.

By the time I got to high school, I was surrounded by everyday guys that were in the neighborhood talking and preaching about Black history and the importance of Black history. I was certainly influenced by them. David Butler, his name is Dawud Hakim, had a bookstore on 52nd Street right on Walnut and 52nd Street. It’s still there. His daughter manages it now. He was a major influence on my life, teaching and talking about African history and African-American history. Cybil Lester was a teacher and activist that used to come into the neighborhood. He would write all these different papers and positions on race, and about lynchings and hangings and beatings. He would talk a lot about the Negro, and about Joel A. Rogers and Carter G. Woodson. I was a teenager in the neighborhood and these guys would venture in while they were waiting for their girlfriends, and they would take the time to talk to me and some of the kids. I’d stop playing wallball, I’d stop playing basketball; I wanted to hear what they were saying.

When I left West Philadelphia High School and went to the University of Pennsylvania, there were a number of doctors that I think saw something in me, and I was inspired by them. When I went to Children’s Hospital, my mentors were Dr. Leonard Bachman, director of the Department of Anesthesiology. He eventually became the secretary of health for Pennsylvania. Dr. C. Everett Koop, who later became the surgeon general of the United States, was one of my major, major mentors and promoters. There were so many things that man allowed me to do and pushed me into doing. I was surrounded by a lot of different forces.

How was your experience at the School of Medicine as an employee and student in the 1950s?

It was more the Medical Center than the Medical School, but I frequented the Medical School. The University of Pennsylvania, as well as most medical schools and medical institutions, practiced racial segregation, racial separation, and had racialized medicine and medical care. There were few, if any, Black doctors or Black nurses. Blacks were more likely to be on wards as opposed to private rooms. The blood was segregated. It was marked ‘C’ and ‘W,’ colored and white. Black people ate in the basement for lunch; white people ate in the first-floor main cafeteria. Even the Black people who cooked the food couldn’t eat in the same cafeteria. Black people had an inferior insurance policy to what white employees had. Very few Blacks were in jobs beyond housekeeping, kitchen workers, laundry workers, lunchroom aides, orderlies. There may have been a few technicians. I spent those years fighting to desegregate all of that at Penn.

What I tell young doctors now is the Medical School was all-white and all-white male. Today, there is a lot of diversity among the doctors and there are more women doctors than men doctors, or equally as many women as there are men.

In 1955, when you were in your early 20s, you established the WD Palmer Foundation and the Black People’s University of Philadelphia and Freedom School. Can you talk a little bit about both organizations?

The Palmer Foundation was created to be a research center on issues relevant to the Black community: African history, African-American history, American racism, American history, information gathering of Black people in terms of health care, housing, education, employment, business—anything and everything that would could gather.

The Black People’s University of Philadelphia and Freedom School was the advocate group and teaching arm for the Palmer Foundation. The Palmer Foundation would gather data in terms of political organizing, grassroots organizing, and the Black People’s University and Freedom School would teach grassroots organization. The Black People’s University was a tool for teaching people from preschool all the way to senior citizens about leadership, self-development, and social justice.

I didn’t really name or identify it as Black People’s University and Freedom School until 1955, but I would hold court on a bench in front of our house and on the steps in the neighborhood, and I would talk to my friends and the young kids in the neighborhood about the history of Black people. By the time 1955 came around, I kind of formalized it with a name. I didn’t have a place, but I had a name. Eventually, I would get a place, around 1960.

You have to imagine how bold an initiative it was in 1955, when the idea of even using the term Black was offensive to Black people. They did not want to be called Black, which is why I did it. And nobody gave me the authority to name it a school.

The Black People’s University of Philadelphia lasted from 1955 to 1985, and the Palmer Foundation is still ongoing.

How did you end up at CHOP?

I went to Children’s Hospital in 1957 and became director of the Department of Cardiopulmonary Therapy. It was the Department of Respiratory Therapy; I turned it into the Department of Cardiopulmonary Therapy. I became the youngest director in the country at 24, 25 years old, and the only Black director in the country. I would stay at Children’s Hospital for the next 10 years, from 1957 to 1967, and I continued to run the Palmer Foundation and the Black People’s University and Freedom School.

My Children’s Hospital experience was formidable. I had income to help finance my projects. I was paid top dollar. I was taught by my mentors at the University of Pennsylvania that you had to negotiate the top dollar to run the department. Throughout all this, I experienced racism, and discrimination, and separation, and the foibles that go along with this pandemic of race called racism. Eventually, I called Children’s Hospital out on its racialized behavior.

What kind of work did you do at CHOP?

I was not a medical doctor; I was a medical specialist. I was a certified specialist. I played a major role in a number of things that took place in the field of medicine.

I helped develop hypothermia units to help control the temperature in children and babies with a temperature in excess of 104 degrees. I worked with Forrest Bird and helped to perfect the Bird respirator. We test-used it at Children’s Hospital as one of our devices for sustaining life in premature babies to adolescents.

I worked on a number of the developments on oxidation tents and ventilators. Various companies would seek me out because they wanted to get into the pediatric market, and I was open to trying to find new ways of providing comfort from incubators, oxygen tents, hyperbaric chambers.

When [former President] John Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy had their child Patrick [in August of 1963], he was born prematurely with hyaline membrane disease. I was the go-to person. They were trying to fly me to Massachusetts, where the child was, but we couldn’t because time was of the essence, so we sat for a 24-hour telephone consult. Myself, Dr. Leonard Bachman, Dr. Jack Downs, and Dr. Charles Richards from anesthesiology worked closely with the doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital to try to stabilize the child. [The newborn lived for 39 hours.]

Why did you decide to leave the field of medicine?

Well, I think that I put so much time into the Civil Rights Movement, the Black Power Movement, the Afrocentric Movement, the Black Liberation Movement, that it was beginning to be a conflict. I eventually called for a strike against Children’s Hospital in 1966, the year before I left, to shut it down because it still was not totally deracialized, certain departments and certain behaviors. And the thing of it is, I enjoyed carte blanche access to the administration, to the top doctors. C. Everett Koop opened up doors for me, and as his name grew, it gave me real cachet, but I couldn’t walk away from the racialized behavior.

Children’s Hospital was good to me and gave me many, many opportunities. While I was at Children’s Hospital, I went to Temple University for two years to work on a social science and business degree. After that, I went to Cheyney State University to work on my education degree. I would eventually leave Children’s Hospital after shutting it down. I went to North Philadelphia to become the director of grassroots community organizing for the Model Cities Program, a $50 million grant program to try to rebuild North Philadelphia.

Black high school students gather in the courtyard of the Board of Education Building during the Philadelphia school strike of 1967. (Image: George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection at Temple University Libraries, Special Collections Research Center)

You were one of the organizers of the Philadelphia student strike or walkout in 1967. How did the student strike come about and what were its goals?

In 1967, young Black students were taking on the mantle of Blackness and Afrocentrism. They were changing their names, and letting their hair grow natural, and wearing dashikis, and speaking Swahili, and learning how to play the drums. My expertise early on as a teenager in organizing was well known, and these students came to me and asked if I would be willing to help them make the case for their beliefs. They wanted Black history taught in schools. They wanted recognition as students. They wanted a student bill of rights.

I had them bring representatives from every high school in the city, every school where there were Black students. I had them bring gang members from their neighborhoods so we could work with them. We worked for weeks, training them, organizing, showing them how to create these networks. We put together a 100-page pamphlet, the story of African Americans told by African Americans. We were sometimes in the basement of Black People’s University until midnight, copying it, printing off materials for them to take into the neighborhoods. We had Black history lessons every Saturday. We had a thousand people on every corner in the city, in all the Black communities. And then we called for a school strike on Nov. 17, 1967.

We wanted every student to leave the building at 10 o’clock. We wanted the schools to be completely empty. And we pulled it off and it became the largest school strike in the history of American public education. Five thousand students marched down to the Board of Education and surrounded the Board of Education to support their leaders, student leaders and adult leaders that were negotiating 25 demands. And they got all 25 demands—but not before they were attacked by the police, who dragged them in the streets, and beat them, and jailed them. I was arrested for conspiracy, mayhem, riot. The children were taken off to jail, and the whole city exploded. Young people all across the city were breaking windows in downtown Philadelphia and overturning cars because they reacted—rightly so—to the atrocities of the police attack. They police attacked us with tear gas as well. They were trying to use that as cover to get to me. Eventually, I went to jail. I had gone to jail a lot when I was younger, but I found out as I got older that going to jail was not always a bad thing. It all depends on what you go to jail for. There are good things to go to jail for, as well as bad things.

If you don’t mind, can you tell me more about your conversation with Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, two weeks before his death? What did Black youth in the city want you to talk to him about?

The Young Afros were a group we had created in Philadelphia. These were young people from every section of the city, largely gang leaders that we converted into being community activists. Their position—like many people in the Black Power Movement and many in the Civil Rights Movement—was that they were not pushing for integration. What they wanted was desegregation. The difference is integration forces races to intermingle. Many Black people thought that should be an option and not a requirement. They wanted the right to be able to go anywhere and do anything, and be treated the same way, but they wanted to choose whether or not they wanted to go into a school, or a restaurant, or into another neighborhood to live. That was one was one of the major things they wanted me to talk to King about, his push for integration, because we were talking about solidarity in the Black community and rebuilding the Black community, and that was not going to happen unless you focused on the Black community.

The other thing they wanted me to talk to him about was his stance against the Vietnam War. We were all against the war in Vietnam, and King took a very strong position against the war. They wanted to make sure that he stuck with it because [former FBI director] J. Edgar Hoover had dossiers on a number of people, including Dr. King, and almost all of the activists. All of our names were on the FBI files, and some of our names were on the CIA files as well. The Young Afros didn’t want King to relent on his anti-war stance because Hoover was trying to disclose an extramarital relationship that King had. They wanted me to counsel him, conjoin him, to convince him not to back down no matter the consequences. Those were the two major things.

The interesting thing is when we finally met at the Episcopal Church, Rev. Jesse Anderson’s church at 52nd and Parish streets, Jesse put King and I in the anteroom. There was a large congregation waiting to hear him speak, and they wanted me and him to get together before he spoke. That was not the first time I had met him but it was the last time that I saw him. He was tired, and he looked tired, and I conveyed that to him. I said, ‘You really look tired,’ and he said, ‘I am.’ I know that there were times when he wanted to quit, when he wanted to leave the movement, and he tried, but he was really overwhelmed by the people begging him not to quit.

I did not push him on the integration piece when we spoke, but I did counsel him, push him on the war, to keep his anti-war stance no matter what the consequences. And the implications were clear, and he knew what they were. The Young Afros were waiting outside. They didn’t come in the church and they didn’t come in the anteroom, it was just me and him. They were waiting outside for me to come out. I suspect they were waiting for me to come out and report what went on. Well, I went out and I never told them what the conversation was. The bulk of that conversation was about him getting rest, that he could not continue down that path because he looked tired and he was tired. And two weeks later, that last sermon of his really told the whole story of how tired he really was, and that he saw that this was a path that would lead directly to his death. I don’t think I’ve told that story to anyone else, other than to you now, other than on TV in preparation for a King Day event about five or 10 years after he died.

Why were you and other activists in the movement so strongly against the Vietnam War?

The war, like so many things, exposed the contradictions of the society in general, particularly as it related to Blacks. Blacks were being drafted into the war at a very high rate and Blacks were disproportionately being put on the front lines. Blacks were looking at the contradiction of fighting brown and tan people who they had no quarrel with, and were seeing the contradiction in terms of race in America and its racial behavior toward other people who had brown and tan skin around the world. It wasn’t a war that was any of America’s business.

You mentioned that a lot of Black activists were monitored by the FBI and CIA—a lawless FBI or CIA at that. Is that something that concerned you, being followed or harassed or neutralized by the FBI or CIA, or did it just come with the territory?

It just came with the territory. I never worried about it. I was just talking about this to a youth advocate group and I said, ‘I didn’t have the normal fears.’ You had to be in it to win it, and I was in it to win it, so that meant paying the price. That meant going to jail, that meant being confronted, it meant being attacked, it meant even being killed. You don’t want these things to happen, but you can’t surrender to those things, otherwise you won’t do anything. I think that’s why most people don’t do anything.

You went to Howard University Law School in the late 1960s at age 33. What motivated you to become a lawyer?

What happened was I was very active in these movements. I would take actions and go to jail and get locked up, and my lawyers were always telling me not to do things. I said to them, ‘I don’t want you to tell me what to do and what not to do, I want you to defend whatever I do, whatever I choose to do, because I’m trying to make a case, I’m trying to make the point.’ So I just got frustrated and said, ‘I’m going to do this myself.’

Who were some of your allies at the time?

Bill Meek was a social worker in the city. Cecil B. Moore was a lawyer/activist. He led the fight to desegregate Girard College. David P. Richardson, who I trained, became a state representative when he was 24. He was the youngest state representative in the history of Pennsylvania. John F. White, Jr. became the secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Welfare. Lucian Blackwell, Jannie Blackwell. Lucian was a state legislator who became a city councilman and then later became a U.S. congressman. When he became a congressman, his wife was elected to his council seat. Stan Straughter was the head of the Mayor’s Commission on African and Caribbean affairs. Mattie Humphries. She was an unbelievable and extraordinary person, and had certifications and degrees in nursing and health care and health care administration, and at age 60 or so, she went to Villanova Law School to get her juris doctorate. Father Paul Washington. I trained Paul Washington, I recruited him.

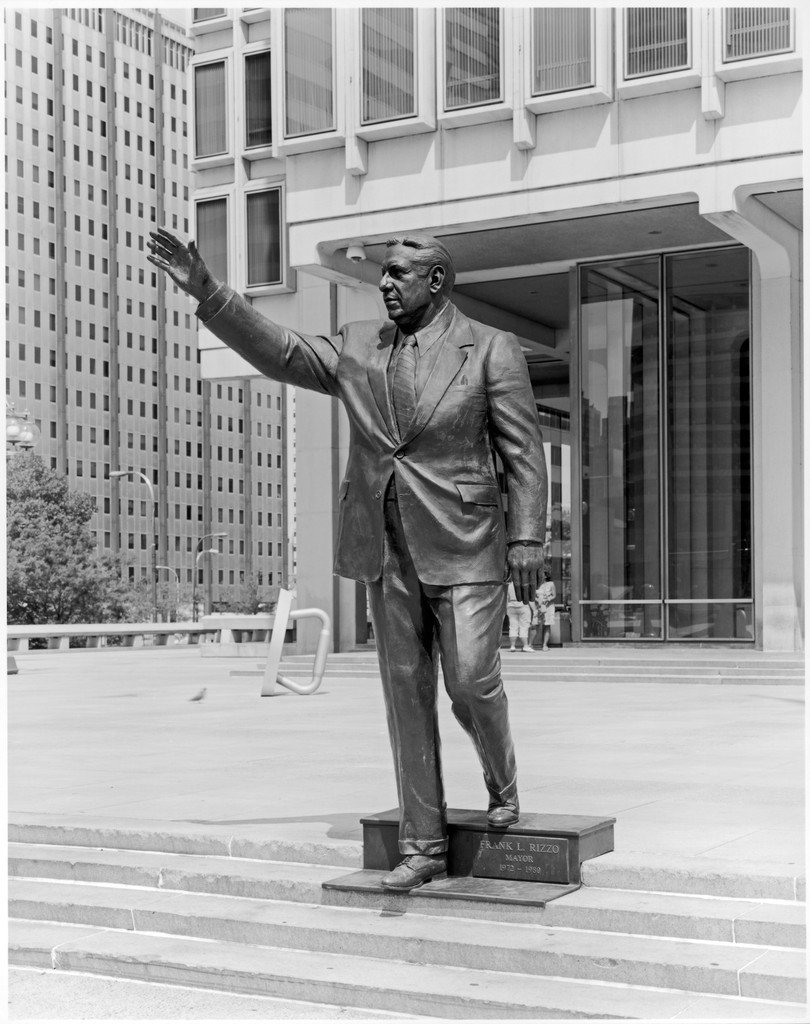

You were active during the Rizzo years, the two-term administration of former Mayor Frank Rizzo. Rizzo has been in the news in the past year or so regarding the removal of his statue across from City Hall. What are your thoughts on Rizzo?

Rizzo was a complex guy. Rizzo was a cop for years and Rizzo allowed a lot of people in South Philadelphia—Italians—to have speakeasys and to have some prostitution, et cetera, and he blinked his eyes. He let them have that, but he was opposed to drugs. He really loved the neighborhood, he loved the community, he loved the city. He had many, many friends in the Black community and he allowed the numbers writers in the Black community and the people who had speakeasies, and prostitution, he allowed it to go on in the Black community, too. He had a tremendous following in the Black community. That’s why Black people were really outraged when he attacked the children [as police commissioner] during the school strike, because they couldn’t defend him and all the good stuff he’d done. In fact, when he became mayor, he hired more Blacks in his administration than all the other white mayors combined throughout Philadelphia history. A lot of folks don’t know all this stuff. In 1991, he was coming back for a third term, and he was going to win. One of the reasons he was going to win was because all the Blacks that had supported him before the school strike supported him again because time had passed since ’67, but he died before the election could take place.

Just so I’m clear, do you think Rizzo gets a bad rap these days?

Well, I think what happens is people don’t have a full history of any of us, so their take on who any of us are or who they think we are is skewed by their lack of knowledge of who we are and who we might be. And I think Rizzo falls into that category as well. What he did during the school strike was hideous, there’s no question about it. And I’m told that his policemen were trying to kill me. I don’t say that he ordered them to kill me, but I think there was frustration about my ability to do what I was doing. One time, Rizzo said that no person— meaning me—should have that much power to shut a whole city down, to shut a whole school system down.

You did a lot of political organizing in Atlantic City in the 1980s. Why did you decide to return to your place of birth?

Well, my uncle called. My mother’s family was all born in Atlantic City. My uncle was a captain in the police force and was one of the first Black motorcycle policemen, and he would constantly contact me to come in and run campaigns. My uncle was involved with the James Usry campaign. We worked to do a recall of a sitting mayor, which is a tough thing to do, and we were successful in recalling the mayor, Michael Matthews. After the recall, there was a runoff, and James Usry was a Black candidate. And they called me back again. We were able to get him elected as the first Black mayor of Atlantic City since 1854. Each time they wanted to get people elected, they called me back, so I commuted back and forth for years, running most of the campaigns in Atlantic City.

After the Usry campaign, I ran the campaigns for my uncle. I got him elected as a city councilmember, but he died before he was able to serve. For 20 years or more, I ran most of the campaigns in Atlantic City to elect a Black government, which was almost a duplicate of what I did in Philadelphia. In Atlantic City, I utilized the expertise I got from helping to create Black governments in Philadelphia, both in electoral politics and appointed politicians.

As a former political organizer and longtime advocate for equality and racial justice, can I ask your thoughts on Donald Trump and the Trump administration?

I didn’t think Trump was any worse than a whole bunch of others. All down through history, we’ve had people who have politicized Black people and poor people and white people. So that was nothing new. He was an opportunist like so many others. President [Woodrow] Wilson had a private showing of D.W. Griffith’s ‘Birth of a Nation’ in the White House. And he came away from it and publicly concluded that D.W. Griffith was correct, that Black males were predators and were out to destroy white women, rape and attack white women. That gave rise to the Ku Klux Klan, who ran across the country, North and South, killing Black people just because they were motivated by that movie.

Can you talk about your teaching career at Penn? When did it begin?

I came to Penn in the 1960s because of student activism. I was an activist that was informally teaching on campus. The students recruited me and we set up a school without walls in the 1960s, 1962 or so. Every week, we had a school without walls and a community exchange, where I brought in activists from all around the city and around the country. Once a week at College Hall, we would engage students and faculty that wanted to learn about the struggle, the fight that was going on outside the walls of the University.

Over 50 years ago, in 1969, I founded the required course on American racism at the School of Social Policy & Practice. I was one of the engineers, one of the advocates for that, along with the student body. I engineered that by organizing students at the school, and the limited number of faculty that supported it, and bringing in neighborhood and community people into the school to push that agenda. Penn’s School of Social Work was the first school in the history of American academia to have required courses on American racism for a graduate degree.

My primary placement is at the School of Social Policy & Practice. I’ve been an adjunct professor there for 30 years. I also created the Black Men at Penn SP2 council and the John Hope Franklin Combating American Racism Award. I was one the cofounders of the National Association of Black Social Workers, and we have a chapter here at Penn.

I have also been a vising lecturer in Medicine, Law, Education, Urban Studies, African Studies, History, Wharton, and the School of Engineering had me doing a course one time for their school.

Last fall, I was able to get the Medical School to have a course on race, racism, and medicine, which I ran for 10 weeks. This September, we’re going to do it again and possibly do two classes. It covers displaced populations and all the fights I had against all the colleges around gentrification. It’s a course that will continue. Urban Studies has also allowed me to teach a course on displaced populations.

I have 16 Penn interns working with me at the Palmer Foundation. I continue to engage in neighborhoods and communities around the city and around the country to share this information and these tactics and these strategies and this training to develop leadership—political leadership, community leadership.

You were one of the leaders of school choice movement in Pennsylvania in the 1980s and 1990s, which gave rise to charter schools, and you led a charter school for more than a decade. Why do you support school choice?

It’s called parental school choice. It’s parents choosing for themselves. Parental school choice says a parent should decide if their child wants to go to a public school, a private school, a parochial school, a Christian academy, a home school, a charter school, a cyber school, because nobody knows what’s best for their child’s education better than the mother and father. Parents should be able to pick and choose where their children go to school. They shouldn’t just be automatically forced into a government school. I think the government owes every parent an opportunity for their children to be educated, but the parents should pick and choose where the money that is set aside for those children is spent.

This is a very hot-button issue in 2021.

I went through the public system and I watched the public-school system deteriorate. The push for parental school choice has been around the 1960s and ‘70s. I was an advocate for homeschooling all the way back when I opened my Freedom School. And then in the 1980s, as the movement started to grow and it needed some traction, I joined the movement to create opportunities for parents.

For the most part, a lot of the people who fight against parental school choice are the people who have their children in better schools. The question I always ask white liberals and Black accommodationists is, “If you pick the school that your child goes to, what makes you think that poor people—in particular, Black people—shouldn’t be able to pick the school that their child goes to? It’s only because of your own arrogance about who you think they are. If you really think that the public schools are going to get better, why don’t you put your children in a public school, and you move into the houses where poor people live, and they will move into the houses where you live and go to the schools that your children go to. And when the public schools get better, you can switch places again.’ How many people do you think would take me up on that? None. That’s the arrogance of elitism and privilege, Black or white privilege.

Black people have been protesting almost continuously over the past several years, usually in response to police killings of unarmed Black men and women. As someone who has been protesting much longer than most of the protesters have probably been alive, is there any advice you would give to them?

It’s wonderful that people raise up and protest, but protests really only highlight a problem. The question is, who is going to be around and help change the problem? Who’s going to do the organizing? Who’s going to do the planning? Who’s going to do the legal construction? Who’s going to be around to enforce it? Who’s doing the training for people in those movements to accommodate all those things I just said. People think if they go to a demonstration or a picket or a sit in, that somehow they are part of a movement. Well, they are, but that’s the low-fruit part of the movement. The real hard work is the aftermath. How do you organize and sustain the consciousness you brought to the movement by picketing and demonstrating? What’s the endgame?

Did you follow the Chauvin trial?

I did, to some extent. It’s the same old merry-go-round that I’ve been on for the past 87 years.

What did you think of the verdict?

Nothing. Nothing. Nothing more than it’s just this one now and they’ll be another one, and another one, and then another one.

Philadelphia has a growing gun violence epidemic. You brought together gangs in the city in the 1970s to deal with the growing violence. How do you think the city can resolve the gun violence crisis?

I think a lot of it has to with education, a lot of it has to do with employment, a lot of it has to do with being able to help people live a decent or better life. Some people have the attitude of, ‘If I can’t make it, I’ll take it, and if you’re doing everything you can to block from being successful, then I’m going to find any easier way.’ We used to take the gang members and have classes for them at 1414 South St. We had them come in, and we had them put their guns away. We would do it by neighborhood. We had a crate and they would put their guns in the crate by neighborhood. You have to be embedded in them and they have to trust you. People need to know that you care about them. You have to love people. People have always known that I have abiding love for people in general, Black people in particular, and for older people and young people, even more particular. Without that abiding love, you can’t connect to them. They know whether it’s genuine or not, whether it’s real or not. That’s what has always kept me in my staid. Folks find their way to me or are attracted to me because of their sense that I really care. And I think a lot of young people think there’s no caring.

We’ve taken self-worth away from young Black people. We’ve pushed them into a state of nihilism, as state of utter self-hatred. And Black-on-Black crime, as far as I’m concerned, is a product of that. And no one wants to talk about it.

Can you talk about your petition to get the government to declare racism a national public health crisis? What is your goal?

I started this petition to require the government to declare racism a public health crisis. The goal is to get a million signatures before the end of the year. Declaring racism a public health crisis is the end of racism. That’s the end of systematic racism. All people should sign it. We’re pushing the government to do it to end racism in America. That is the endgame. Make racism a pandemic. And then I will ask Congress to create a national, long-term, structured dialogue and debate on race and racism in America—the conversation that white people have never wanted to have, and the one that many Black people run from because it’s too painful to go through it.

Making racism a national public health crisis brings everything into the fold. You have to put in everything, you have to put in the lynchings, you have put in the beatings, you have to put in the poor literacy rates and the dropouts. You have to put in the hunger. You have to put in police violence. You have to put in all the things that Black people have suffered for the last 400 years.

What keeps you going? You’re 87 but you don’t seem like you’re slowing down at all.

I’m not, I’m revving up. What keeps me going is the fight, and that fact that it’s unending. And I don’t expect it to end in my lifetime, but I expect to keep on fighting for the rest of my lifetime. And I expect to keep on trying to recruit and train other people.

Credit: Source link