Fee Waybill hadn’t actually been asked to give a eulogy when friends and family gathered at Our Lady of Mercy Church in Merced, California, to pay their respects to the memory of Rick Anderson.

The Tubes bassist had died on Dec. 16, 2022, after being too ill to join his bandmates on the road that year as they dusted off classics as timeless as “White Punks on Dope,” “She’s a Beauty” and “Talk to Ya Later.” He was 75.

“It was a really Catholic funeral,” Waybill says. “And they didn’t want anybody to speak. But they asked me to read a prayer. And before I started, I said, ‘Well, I have to say something.’”

Having formed the Tubes some 50 years ago in San Francisco by consolidating members of two Phoenix bands — the Beans and the Red, White and Blues Band — Waybill says he felt more like a brother than a bandmate of Anderson.

Interview:Fee Waybill on the Tubes and growing up in Arizona

‘He was so happy that he got to do this’

Waybill and fellow founding members of the Tubes, Bill Spooner, Prairie Prince and Roger Steen, had served as pallbearers.

“So I talked about Rick,” Waybill says. “And one of the things I said was he never complained. We’d show up at a gig and there were no dressing rooms. Or the stage was too small. Or they didn’t have the onstage monitor mix they were supposed to. Whatever the problem was. I can’t remember him ever complaining.”

There’s a reason for that, Waybill says.

“A couple times he told me, ‘This is all I ever wanted. I just want to be in this band and play music.’ He was so happy that he got to do this.”

Anderson had other interests, from restoring vintage cars and trucks to handcrafting improvements to the home he shared in Merced with Marina, his wife with whom he fell in love in the ‘80s and raised daughter Marina Mignon.

From the time he learned to play guitar, though, there was never any question as to what he would do with his life.

As Gregg, his youngest brother, says, “He pretty much went, ‘Yeah, I want to do this.’”

When he wasn’t playing with the Tubes, he often sat beneath a Chinese maple in his garden playing acoustic guitar. He also liked to get together with musicians from the neighborhood.

When the Tubes shared the news of his passing on Facebook, they wrote, “Rick brought a steady and kind presence to the band for 50 years. His love came through his bass.”

What was Alice Cooper like in school?Friends and bandmates share their stories

‘He was part of the puzzle that made it all work’

Steen says the Tubes are like family.

“We’ve been playing together since the early ’70s, lived in a house together for a while, just did nothing but be in a band,” he says. “And Rick was an integral part of the Tubes. He was part of the puzzle that made it all work. And he was just the nicest guy to be around.”

Waybill says, “We’ve been together 50 years, and Rick was always there. He always had his (expletive) together. It’s just devastating.”

Alice Cooper bassist Dennis Dunaway speaks glowingly of Anderson’s abilities.

“He was an excellent bassist,” he says. “The Tubes music, as you know, isn’t simple to play.”

He also brought an offbeat sense of humor to the table, a quality Dunaway first noticed in the ‘60s, when he’d hang out with the Beans in Phoenix.

“Musicians tend to be quirky and he was one of the quirkier ones I’ve known,” he says. “He’d make you laugh and scratch your head a little at the same time.”

When the Tubes realized something was up with Rick Anderson’s health

The first sign that something was off was in May when they scheduled a rehearsal in San Francisco to get ready for a tour on which they planned to play the “Outside Inside” album, a 1983 release that spawned their highest-charting single, “She’s a Beauty.”

As Waybill recalls, “Rick called Roger and said, ‘I’m on my way, but I don’t really feel good. I don’t know what’s happening, but I’m gonna turn around and go home because I’m worried.’”

At home, he tested positive for COVID-19.

“It took him a while to recover from that,” Waybill says.

They rescheduled rehearsal for June.

“And he was kind of in a fog,” Waybill says. “But he played perfectly. He had rehearsed all those songs. And the deeper album cuts from ‘Outside Inside,’ we had never played those live. But he had them down.”

The other Tubes could see that Anderson was in no shape to tour the way the Tubes are used to.

“The way we operate now, it’s pretty tough,” Steen says. “It’s not as though we’re flying private jets and being bussed around in limos. You’ve got to be healthy. And he didn’t look good. We said, ‘Rick, we’re worried about you.’”

Waybill says they did their best to talk him into getting help.

“We said, ‘Rick, go see a doctor, OK? Do everything. Test everything. Just find out what the problem is. You’ll always have the gig with us. We’ll cover it. Don’t worry.’ He goes, ‘Oh, there’s no good doctor here.’ I said, ‘Go somewhere else. Sacramento is right up the road.’”

The bassist had developed a mistrust of doctors 10 or 15 years ago after developing what Waybill calls “a mysterious illness.”

That time, he couldn’t remember the songs, so he went to the hospital.

“And they never figured it out,” Waybill says. “So that kind of instilled in his brain the fact that, ‘Hey, these people don’t know what they’re doing in Merced.’ Then all of a sudden, he was fine. Everything came back. And he played with us another 15 years or so.”

‘The last man standing’:Micky Dolenz reflects on his life as the only surviving Monkee

Rick Anderson’s days on the Phoenix high school band scene

Mitch Anderson recalls his brother getting into music in the early ‘60s, drawn by the British Invasion and the California surf-guitar sound.

“Rick was in high school and discovered a friend that only lived a couple of blocks away was into music,” Mitch recalls.

Soon, he was borrowing Mitch’s guitar.

“I was trying to take guitar lessons but didn’t really devote any time to it,” Mitch says. “So he kept taking my guitar.”

That neighbor kid, Ed Black, went on to play with Goose Creek Symphony and Linda Ronstadt. At the time, though, he and Anderson were just teenagers teaching each other to play by mastering their favorite surf-guitar licks off the records.

Prince was in his freshman year at Central High the first time he saw Anderson, a senior at the time, performing in the auditorium.

“He had an early band called the Radicals,” Prince says. “And from the get-go, I knew this guy had so much charisma. I thought, ‘Hopefully I’ll get to play with him someday.’ And then I did.”

Anderson went on to join the Caravelles, who morphed into the Holy Grail. He and Black also played in the Superfine Dandelion before Anderson joined the Beans.

The Beans and the Red, White and Blues Band move to San Francisco

By 1969, the Beans and the Red, White and Blues Band were two of the Valley’s most popular bands.

Then Prince got a scholarship to the Art Institute in San Francisco, convincing the Red, White and Blues Band, which also featured David Killingsworth and Steen, to come along, recruiting Waybill to drive their equipment in a Divco milk delivery truck.

A year or so later, the Beans, whose ranks included Spooner, Anderson and future Tubes Vince Welnick and Bob McIntosh, followed suit.

“Everybody knew that we were loving San Francisco,” Waybill says. “This was right after the Summer of Love, so it was Hippie World.”

After playing the World’s Fair in Japan, the Red, White and Blues Band parted ways with Killingsworth and placed a “bassist wanted” ad in either Rolling Stone or the Haight-Ashbury Free Press.

“They auditioned all these different bass players,” Waybill recalls. “And they just couldn’t cut it. We went through one after the other, like, ‘No, you can’t handle it. No.’”

‘Painful and delightful’:Graham Nash mourns the music ‘lost’ in feud with David Crosby

When the Beans became the Tubes

In the midst of all those failed auditions, the Beans invited Steen and Prince to join them on a college gig.

“Bill had written a musical,” Steen recalls. “So Prairie and I went along as bit players. That seemed to work. So then we did another show in Phoenix. And it just sort of escalated from there.”

It was Spooner who suggested giving Waybill, then a roadie, something more to do than schlep their gear around.

As Prince recalls, “Bill Spooner said, ‘Well, why don’t you start singing? We can dress you up and do these theatrical numbers with you as the frontman.’”

Soon, they were building a fan base on the strength of their increasingly theatrical performances, inspired in part by growing up in Arizona.

“It was too hot outside,” Steen says. “So we were inside watching TV and it got into our consciousness.”

Prince says. “Our parents all loved Busby Berkeley and the big dynamic shows of the ’30s and ’40s. And we always thought it would be wonderful to comment on what was going on in the culture in more of a theatrical way with dancing. More like a circus.”

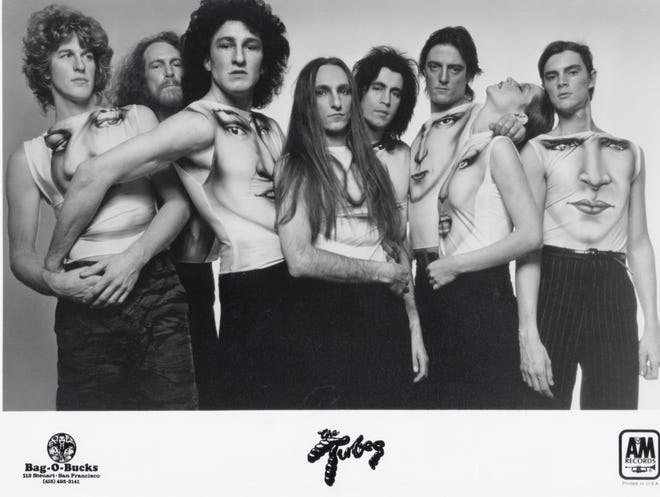

The Beans became the Tubes in 1972 to avoid confusion with an East Coast band that had the same name.

The days of ‘Mondo Bondage’ and ‘White Punks on Dope’

Anderson’s parents enjoyed all the envelope-pushing theatrics of the Tubes.

“Unlike a lot of parents from the ’50s and ’60s, my parents were pretty open-minded,” Gregg says. “They kind of came out of the beatnik generation. So they loved that the band was outrageous. A lot of parents would have cringed at all the sexual innuendo.”

As their show grew more outrageous, it got to where the labels could no longer look away.

“We actually started making videos of our shows,” Steen says. “And that’s kind of what got us signed.”

In 1975, A&M Records released their self-titled debut, which included such crowd-pleasing staples as “What Do You Want from Life?,” “Mondo Bondage” and “White Punks on Dope.”

Hiring Kenny Ortega as their choreographer, they hit the road with dancers and a show that came to focus more on Waybill’s antics.

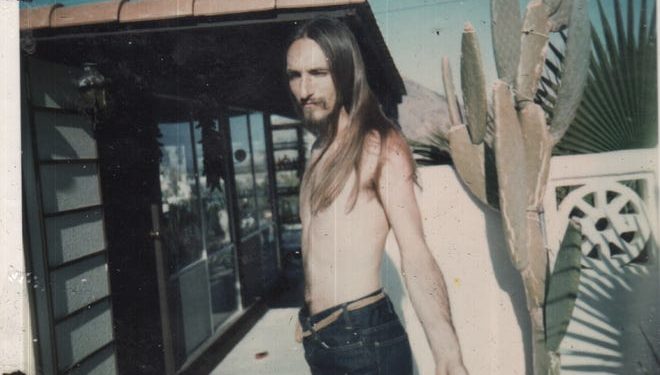

“Originally, we’d dress him up and have him come out, do one song, and people thought it was funny,” Steen says. “Then we kind of developed that whole idea. And Rick was there all the way. He had a very distinctive look. He was a character.”

In addition to his musical abilities, Anderson brought his own sense of style to the Tubes.

“Sometimes, we would have a group outfit,” Waybill says.

“But if we didn’t have some kind of mandated wardrobe, Rick used to wear this Ramones shirt, which I thought was great, under a black motorcycle jacket. And he had, like, a cap Marlon Brando would wear in ‘The Wild One.’ So he had his own look. But when we wanted to do something band-wise, he was right there.”

The Tubes spent the ‘70s touring the country with barely clad dancers and sex toys as part of what Rolling Stone magazine later looked back on as “one of the wildest stage shows in the business (verging at times on soft-core pornography).”

Their shows would often get shut down by the authorities

‘It wound up sort of being a badge of honor,” Gregg says, with a laugh. “Like, ‘Will they shut us down tomorrow night in Cleveland?'”

The Tubes hit the mainstream with ‘Completion Backward Principle’

After releasing four albums to little avail, the Tubes were dropped by A&M, signing to Capitol Records, where producer David Foster helped refine their sound for radio on “The Completion Backward Principle.”

That 1981 release sent a ballad called “Don’t Want to Wait Anymore” to No. 35 on Billboard’s Hot 100 while the guitar-driven New Wave of “Talk to Ya Later” hit the rock charts.

Two years later, “Outside Inside” spawned their biggest hit when “She’s a Beauty” peaked at No. 10.

It’s now been 40 hit-free years since “She’s a Beauty.”

“I like to say we’ve avoided the curse of success,” Steen says. “We’re still trying. We’re still playing hard. And people see that, and they like it.”

Danny Zelisko has worked with the Tubes many times through the years as a concert promoter.

“They’re in a different class, a different league than most bands,” he says. “They’re clever, funny, salty, saucy, sexy, zany. They’ve always had the whole package. Pure entertainment.”

In 2017, when Alice Cooper reunited with his Phoenix bandmates for a string of U.K. dates, including Wembley Stadium, they brought the Tubes along as special guests.

“I love this photograph Ross Halfin took backstage at Wembley,” Dunaway says. “It’s both bands. And I’m going ‘Look at this. In the mid-’60s, we were all just these unknown musicians with starry-eyed dreams. Here we are all these years later, eight guys from Arizona, that little oasis in the middle of the desert, playing Wembley.’”

What’s next for the Tubes?

The Tubes are hoping to stage a memorial concert for their fallen friend in San Francisco and possibly a second show in Phoenix.

“That’s still kind of in the planning stages,” Waybill says.

As for the future of the Tubes, the plan for now is to keep doing what they’ve done for 50 years.

“This is a real blow,” Steen says. “This is hard. And I don’t know how we’ll recover. But you have to find a way. You have to move on.”

Credit: Source link