In the second part of a two-day special report, Joyce Fegan asked six people to open up about how they left one faith behind, and about their new lives.

And, despite the stereotype that people merely fade from a particular practice of religion, she discovered that each of them has been on a spiritual journey towards the life that is right for them.

In today’s spotlight:

- From Catholic altar boy to the Hare Krishnas – Martin Davis dabbled in atheism and “intoxication”, before he met devotees of the Krishna Consciousness movement while studying philosophy at UCD.

- From Catholic to atheist – Michael Nugent grew up in a typically Irish household but realised in primary school that religion was story-based.

- From private equity investor to Shugendo Buddhism – Justin Caffrey was a Catholic until five years ago when he encountered Buddhism through therapy and meditation.

- From Catholic altar boy to Muslim – Michael describes leaving Catholicism for Islam as “this solid structure collapsing” around him.

- Both Franciscan nuns and ordained Anglican priests – Sister Isabel Keegan and Sister Annmarie Stuart who talk of their leaving one religion for another as a “seamless journey”.

- From Catholicism to Vedānta philosophy – Rutger Kortenhorst’s journey began with a 12-week philosophy course followed by “two whoppers of life-changers”.

- Read part one of our special report – In Ireland today, we are choosing our religion – here.

Martin Davis — from Catholic altar boy to the Hare Krishnas

Martin Davis was born a Catholic and, throughout his early life, he went searching for answers. He dabbled in atheism and “intoxication”, before studying philosophy and finally encountering devotees of the Krishna Consciousness movement.

He also runs Sol Art gallery in Dublin as his “occupation”.

“I was born Catholic. I’m a former altar boy; my parents were religious and I was influenced towards spirituality by my aunt.

“However, around my teen years, I became quite atheistic, was a bit of a sportsman but gradually became more interested in intoxication and so-called enjoying the world,” says Martin.

“After school I went to Holland and tried to live the hippy dream, but returned home after a year quite disillusioned with the experience.

“I got work in an insurance company for a year, but found it incredibly boring and towards the end of that year I reignited an interest in spirituality and Zen Buddhism,” he explains.

With his renewed interest in a faith, he re-sat the Leaving Cert and got a place in UCD studying English, French and philosophy.

“In my second year in college, I returned to an interest in Catholicism and regularly attended Mass.

“During my third year, I met the devotees of the Krishna Consciousness movement,” he says.

It wasn’t that I was discontented after my return to Catholicism. It was more that I found extra answers about self-realisation, the nature of God.

“Krishna is another name for God, which means the ‘all-attractive personality’. Also, I found the practice of chanting on beads every day very powerful,” Martin says.

He also enjoyed associating with like-minded practitioners.

“We no longer took intoxication of any kind and practised a moderate lifestyle, which allowed for more inquiry and absorption in spirituality. And I loved the non-violent form of eating, vegetarianism, which made total sense. And I especially love Kirtana, which is congregational chanting,” explains Martin.

Martin married and went on to have children, who are now devotees too.

“After five years as a practising monk, I got married to my wife, Ishani, in 1989.

“We have two grown-up children, Jayananda who is 30 and Sita who is 26. Both of them are getting married this year, also to devotees,” he says.

Another aspect to his devotion to the Krishna Consciousness movement is working in a vegetarian restaurant and other community work.

“I help with the administration of Govinda’s, a vegetarian plant-based restaurant in Dublin, above which we have our Krishna Temple and I also help in the running of our island community in Co. Fermanagh, where we have a retreat centre for both novices and practising members,” explains Martin.

How would a person become a Hare Krishna or convert to one?

“To become a devotee, you just need to chant the holy names of God. It doesn’t matter which name we call: God, Allah, Jehovah, Buddha or Christ.

“Official members take a vow to chant a certain amount on beads, but the process is open to everyone and the process works best when we practise a simple lifestyle,” says Martin.

In Ireland, the Hare Krishnas are planning to grow their community.

“In the future, we hope to open an eco-community outside Dublin where we can practise a more sustainable lifestyle in respect to Mother Earth.

“Also we hope to open smaller centres around Ireland, especially Cork, because we have quite a few practitioners in the south, but no real centre for gathering,” says Martin.

Michael Nugent — from Catholic to atheist

Michael Nugent grew up in a typically Irish household when it came to religion; people went to Mass, but they weren’t evangelical or too orthodox about it.

In his home, he was always encouraged to ask questions and, later in life, this led him to having no faith in any religion.

“My parents were what I call cultural Catholics. My mother believed in God, but disagreed with the Catholic Church on various issues. My father was philosophically agnostic, but went to Mass and even did some of the readings.

My parents always encouraged me to think about things. They brought me to Mass as a child, but told me that I could make up my own mind when I got older. `

“I also read a lot of books that made me think about the wider world, and religion was one part of that,” says Michael.

It was in primary school when he had his own personal realisation that religion was story-based.

“When I was in primary school, we did a project over one Easter holiday to read the gospels and rewrite them in our own words. As I did that, I realised that the Jesus character was like a comic-book superhero doing amazing feats. From then, I knew that it was all just stories,” he says.

“I see faith as believing something that is not supported by evidence, and I try not to do that. Religion is just one example of faith,” he adds.

Michael describes being an atheist as living “without the simplicity and complications of believing things without reasonable evidence”.

While people who do not practise a faith often return to religion for a rite of passage or when a loved one dies, this was not the case for Michael.

“When my wife Anne was dying of cancer, we tried to live as much as we could for as long as we could. One morning as we cuddled in bed with our cats she said: ‘I’m really going to miss this.’ She then realised what she said and corrected herself: ‘No, I’m not. You’re really going to miss this.’ And that’s what I do. I miss Anne and I remind myself how lucky I was to meet her and live with her.”

Michael still goes to funerals of others and weddings too. He remembers the words from his time going to Mass as a child.

“Many people are there on the same basis as me,” says Michael.

I find myself immersed in a family member, talking meaningfully about a deceased friend, then a priest who didn’t know them spoils the memories by talking about them being in Heaven.

Being an atheist is also about justice and creating a fairer society.

“Atheist Ireland works with the Ahmadiyya Muslim community and the Evangelical Alliance of Ireland to promote separation of Church and State.

“Many people contact or join Atheist Ireland because they feel isolated or discriminated against in Ireland. Two obvious examples are parents who want their children to be educated in State-funded schools without being indoctrinated into religion, and people in the asylum process, particularly ex-Muslims, who are discriminated against because they are atheists,” he explains.

Michael bases his own life on things like “empathy, compassion, co-operation, reciprocity, fairness and justice; not on what somebody wrote in a book centuries ago.”

Justin Caffrey — from private equity investor to Shugendo Buddhism

Justin Caffrey was born a Catholic and considered himself one until 2016. However, Buddhism had always been there in the background.

“In many ways I’ve had a fleeting interest in Buddhism for the last 20 years. I never felt really aligned with the values of the Catholic Church, but the underpinning beliefs I did feel comfortable with. However, I never had a great sense of connection and belonging and that was an emptiness in many ways in the context of religion.

“Growing up in Ireland in the ’70s, I was born in 1975, mine was the last generation to be deeply immersed in a Catholic school upbringing,” says Justin.

His own mother, who is now 86, was a minister of the eucharist, but also a liberal woman.

“She would be very liberal. She is pro a woman’s right to choose and pro divorce and pro gay marriage,” says Justin.

While he was never deeply committed to any religion, a “seminal” point in his life came in 2010, with a terminally ill child.

“In 2010, our son was very ill. He was very unwell for 12 months. Every time I’d walk to the hospital, I’d talk to God asking: ‘Please get us to the other side; I’ll go to Mass.’

There was this frustration that we have to offer something, we have to behave in a certain way to avoid being punished. The conversation had an insidious nature; I had to trade a part of my life to have some sway with God.

“When you have a terminally ill child, you will do whatever,” states Justin.

“When Joshua died, that was a seminal moment for me. I struggled to see where Christianity supported me,” he adds.

This seminal moment in his life led him to therapy and meditation.

“My therapist was a Hindu and part of my therapy was meditation, just this really simple practice of watching your breath, yet this immense complexity of being able to sit with yourself.

“I was using it as a tool without any spiritual essence to it, as many people attest. Even if you come to meditation as an atheist, the spiritual connection to yourself is very powerful.

“It opened me up to my own being and to greater empathy to other human beings. I quit alcohol and became completely plant-based,” says Justin.

Around 2016, he started reading about neuroscience and Buddhism and Buddhist psychology. Then he started reading about Buddha.

“I just felt like I’d come home. I’d already felt so much at home with meditation. If meditation was this beautiful room, Buddhism was the house,” says Justin.

Like Christianity, there are so many different variations of Buddhism. In 2018, he discovered Shugendo Buddhism.

“The Shugendo believe all they need is found in nature — this really blew me away,” he says.

In 2019, he trained with them in Japan, which involved a five-day pilgrimage in the mountains.

“It’s completely experiential. There is complete silence, it’s trekking and hiking for hours, fasting, no bed. It’s a place to meet your own physical limits and your mental limits. It’s really a challenge — you get some water, a miniscule amount of food and you eat it in a minute. The aim is to get through the five days and for nature to be the saviour through all of these challenges,” says Justin.

In 2021, he hopes to return for an autumn ceremony where he will receive his Shugendo name.

From the death of his second son to now, Justin says his life has taken an “entirely new direction”.

“I’ve found a sense of inner peace and calmness that was never there before. Although I can’t stop other people causing me harm, I can notice how I feel about it and notice my own capacity to just sit with it and not be suffering in pain.

It’s a very transformational way to live.

“We are not trying to find joy, though that is a byproduct; it’s about the acceptance of life just as it is and the acceptance of you as you are.

“So much of the experience of human pain is: ‘I’m not good enough, thin enough’. So it’s about accepting yourself as you are,” says Justin.

Having worked in London, building and selling million-dollar companies as an investor, he now works as a coach and therapist.

“I get a lot of work from people who used to work in that life and are jaded by capitalism and the relentless pace of life,” says Justin.

Michael — from Catholic altar boy to Muslim

Michael, 32, was born into a Roman Catholic family, where he attended Saturday evening mass with his mother and sister. He was an altar server in primary school and, with an interest in music, he joined the folk choir.

However, when he went to college, he started questioning his faith.

“I had existential questions that started coming up. My sister growing up had a brain tumour and, before I went to college, my father had bowel cancer and that hit me the hardest. You look up to your father figure and then you see them vulnerable,” says Michael.

While he was in college in Dublin, he would work in a shop in Meath at the weekends. One evening, there was a raid on the shop and he was held up with a butcher knife.

“That affected me a lot. What would have it all been for if I died? It makes you feel very vulnerable to be in a position like that; you go away asking these existential questions,” he says.

He was studying forensic and environmental science and his best friend attended the Royal College of Surgeons (RCSI).

“I used to go over to RCSI to meet him. I’d see him go down praying in RCSI. They have a lot of events with the Islamic society and debates on theology.

“This man is a convert to Islam, he is a friend from home,” explains Michael.

He started investigating Islam for himself and was looking for “holes”, which he could not find. He describes leaving Catholicism for Islam as “this solid structure collapsing” around him.

For him, Islam in particular, appeals to his “heart, soul and intellect”.

“I read the Quran from beginning to end and I also read Martin Lings’ book on the prophet Muhammad. Islam holds true to maintaining how it was 1,400 years ago. There is an integrity of the religion,” says Michael.

While different to his culture growing up, he never found Islam “alien”.

“I felt like it was a form of repatriation; like my parents taught me certain values that were compatible with Islam, like looking out for your neighbours,” he says.

Islam and Christianity are very compatible.

However, he does admit to finding some of the cultural aspects of Islam “hard”, such as who should and shouldn’t be allowed into a mosque or how people should dress.

All the same, Michael is a “traditionalist” and eats halal meat and prays five times a day. He is also a member of New Muslims Ireland, a convert support group.

“I’m very active and proud of my religion. Being Irish and being Muslim is synonymous for me,” says Michael.

This year he will mark 10 years as a Muslim and says “gratitude” is what he mostly gets out of his new religion.

“It’s gratitude, being grateful for what you have. There are so many people suffering and gratitude is a way of alleviating depression. You get a sense of peacefulness in your heart. It’s perspective; people want to know where they come from and where they are going. It’s a question that’s innate in us on a spiritual level, it’s something to tap into,” he says.

While his family has been “fantastic” and very accommodating when it comes to practical things like going to halal butchers, he has lost friends over time. He has also made friends, too.

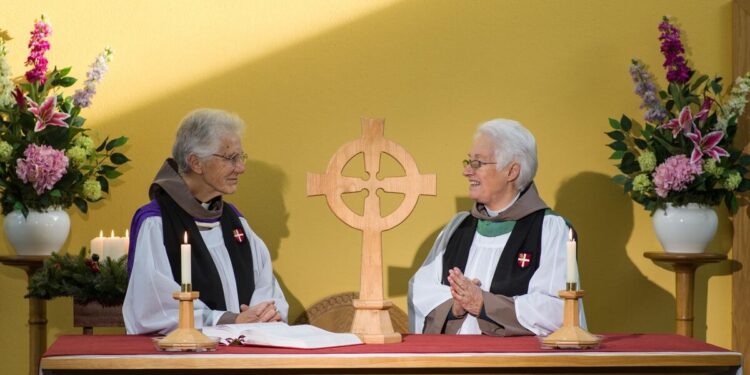

Sister Annmarie and Sister Isabel — both Franciscan nuns and ordained Anglican priests

Sr Isabel Keegan and Sr Annmarie Stuart are Franciscan Sisters who were members of the Roman Catholic Church but are now ordained priests in the Church of Ireland. They minister to the parishes of St Cartach’s in Castlemaine and St Michael’s in Killorglin in Co. Kerry.

Annmarie, 79, had Catholic and Anglican religion in her life from her mother and father. Early on she felt called “to the vowed life”.

“I was born during the last World War. I was evacuated with my mother to Lancashire, to where my grandparents had been evacuated. My mother was an Anglican and my father was a Catholic. When she married, she became a Catholic.

“I was sent at five to a convent boarding school. When I eventually left the school, I felt called to the vowed life. My father was a businessman and lived in Chelsea and that felt alien to me, so I looked for a religious order,” says Sr Annmarie.

She would joined the Franciscan order and studied theology and went to “preach retreats”.

Sr Annmarie met Sr Isabel through the Franciscan order.

“I was born in Dublin. My mother was a devout Catholic; my father went to Mass once a week. Through my father I became very aware of nature; through his eyes, I would look at something beautiful.

I felt my father was a very spiritual man — that was my sense of another life, the birth of another life within me.

“At about 18, I decided to dedicate myself to God. I wanted to give something back to God when I recognised the wonder of God coming among us,” says Sr Isabel.

She initially joined the Sisters of Nazareth, nursing the elderly and the dying, and then changed over to a more “contemplative way of life” in the Franciscans.

The two sisters got work as cleaners in a home for the deaf and the blind. They were living as Roman Catholic nuns in Canterbury, and studied and prayed hard.

In Canterbury, they got to know the Anglican church, and it was from there they became ordained as Anglican priests.

“The Anglican parish priest asked us to be ordained. We were shocked as it wasn’t on our minds because of all the work we had been doing,” explains Sr Isabel.

However, the sisters do not see their journey as leaving one religion for another.

“It seemed strange to leave one organisation for another. At the heart of our journey is this relationship with a living God. My aim is to share who the love of my life is. We follow the gospel of Christ.

“We thought and we prayed about it, how strongly we felt a different way of being Catholics,” says Sr Annmarie.

She adds:

We are Anglican priests. We are Anglican Franciscan nuns. We see it as a seamless journey.

She says that they have both always been “ecumenical in many ways” in their religious lives, with their work being to help people find their way to the living God.

“Some people have nice short journeys, and some people’s journeys demand change and movement,” says Sr Annmarie.

Rutger Kortenhorst — from Catholicism to Vedānta philosophy

Rutger Kortenhorst was born a Catholic, but now follows non-dual Vedānta Dharma philosophy, one of the six schools of Hindu philosophy. However, he does not call himself a Hindu.

During 2020, instead of travelling to India as he does every summer, he translated the Bhagavad Gītā from cover to cover and put it online (https://sanskrit.ie/gita). The Bhagavad Gītā is a 700-verse Hindu scripture.

He says he was always interested in scriptures.

“From a young age I was aware of a deep interest in scriptures. I asked my parents could we read a chapter from the Bible each day after dinner. We started with Genesis and years later we finished Revelations. If my dad was not home for dinner, someone else would read. There was hardly any discussion, but it did go in.

“It was probably prompted by my godmother’s gift of an illustrated Bible for children when I did my First Holy Communion. I really cherished that book and read through it many times. It was in Dutch, a calligraphed text with illustrations by Piet Worm. I still have the book,” says Rutger.

However, by the time he reached 18, he was searching for answers to some of life’s “big questions” and he looked beyond Catholicism and the bible.

“From age 18 to my mid-20s, I was searching for answers to some of the big questions and swung between religious church-going phases and atheism, the born-again Christians and the Mormons,” says Rutger.

They were all morally upright and good people but, unless you signed up to their club, you were doomed to hell and damnation. That put me off each time.

He was eventually introduced to philosophy, which changed everything for him.

“I went to a graduation dinner with a friend who had just graduated from medicine. Her friend asked me during the meal: ‘What is the most important thing in your life?’ I told her how involved I was in some social work, to which she replied: ‘I didn’t ask you what you are doing. Simply, what is the most important thing in your life?’

“I was stuck for words. I felt like a fool that I had been around for more than 20 years and I could not even answer that simple question. To get ‘revenge’, I asked her what it was for her. She looked me straight in the eyes and just replied: ‘Philosophy.’

“She gave me a brochure and the next day I signed up for a 12-week philosophy course in the School of Philosophy and Economic Science. The course had already started three weeks, but I did not care. I was ready. She turned out to be the teacher,” explains Rutger.

Two more life-changing things came his way soon after, in the form of meditation and Sanskrit.

“They were two whoppers of life-changers. I naturally slowed down on eating meat and have been vegetarian for the last 40 years. I cannot explain why that was so natural, apart from it being some effect of sitting down to meditate twice a day for 30 minutes,” says Rutger.

In 1986, the John Scottus School opened in Ireland, which follows the normal curriculum, but students meditate and learn Sanskrit too. Rutger got a job here.

“We were full of enthusiasm. We would meet in school at 5am to prepare our lessons for the day. I was also cast as the exacting dean of discipline, making sure top buttons stayed closed and no one set a foot wrong. We had assemblies every day, we sang hymns and Sanskrit prayers, dedicated and surrendered our actions to the innermost self and paused with the students at the start and the end of each class and meditated twice a day. We still do,” says Rutger.

Rutger explains that he is not a Hindu because a person cannot “really become” one.

“There is no conversion or ceremony like you get in many other religions. It is based on Sanātana Dharma or ‘the eternal law’.

There is no founder. It feels more timeless and universal than a local religion.

“It means practising patience, sense control, forgiveness; using intelligence for the good; body control; self knowledge; non-stealing; truthfulness; purity; and not getting angry. I do my best. It is a tall order, but why not have this as your lifetime’s goal?” asks Rutger.

“When I am in India, I sometimes witness Hindu rituals. I love to see the devotion it brings out in people, but I do not need to take on more rituals. It is the emotion behind them that counts and that emotion is universal,” he adds.

Credit: Source link