In our mezzanine conversation, Marshall told me that the “Rythm Mastr” story line has become increasingly complex. There are now two different groups of people trying to stop the gang violence—Farell and his crew of Afrocentric drummers, and a posse of wheelchair-bound tech wizards, victims of drive-by shootings, who use weaponized robots against gangs. He also said that Chicago is no longer where it happens. “I’ve substituted a city and a world that I created myself,” he said. “It’s invention the whole way. And I don’t think it will take another ten years. It’s possible within the next five.”

In the early two-thousands, a few perceptive curators started to think about giving Marshall a mid-career survey show. Elizabeth Smith, the chief curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago at the time, approached him about doing one. Marshall didn’t want a survey. What he wanted was a show of existing and new works of his that dealt with Black identity and Black culture in white society. This led to “Kerry James Marshall: One True Thing, Meditations on Black Aesthetics,” which opened in Chicago in 2003 and travelled to museums in Miami, Baltimore, New York (the Studio Museum), and Birmingham. Five years later, though, Madeleine Grynsztejn, who had recently become the director of MCA Chicago, proposed doing a full-scale retrospective of Marshall’s work there and he said yes. At Grynsztejn’s suggestion, they decided to wait until he turned sixty. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles signed on to take the show when Helen Molesworth became its chief curator in 2014. The Metropolitan Museum of Art had already agreed to do the same, a decision that helped make the exhibition a major art-world event.

Marshall gave Grynsztejn and Molesworth complete freedom to do the kind of show they wanted, a chronological survey that concentrated on his paintings. They wanted to call it “Kerry James Marshall: Old Master,” but he balked at that. “Kerry didn’t like the word ‘old,’ ” Molesworth confided, smiling. “He came back with ‘Mastry.’ I think he liked playing with the word—what it meant to have mastery, and to misspell it and make it colloquial, and put it in the tradition of African American wordplay.” “Mastry” opened at MCA Chicago in April, 2016. I saw it a few months later in New York, where its seventy-two paintings filled two floors in the Met Breuer, at that time the Met’s modern and contemporary branch. (The building had formerly housed the Whitney Museum of American Art.) For me and for many others, the exhibition placed Kerry James Marshall in the pantheon of great living artists. “One might have thought it impossible for contemporary art to simultaneously occupy a position of beauty, difficulty, didacticism, and formalism with such power,” the artist Carroll Dunham wrote, in Artforum. “There really are no other American painters who have taken on such a project.”

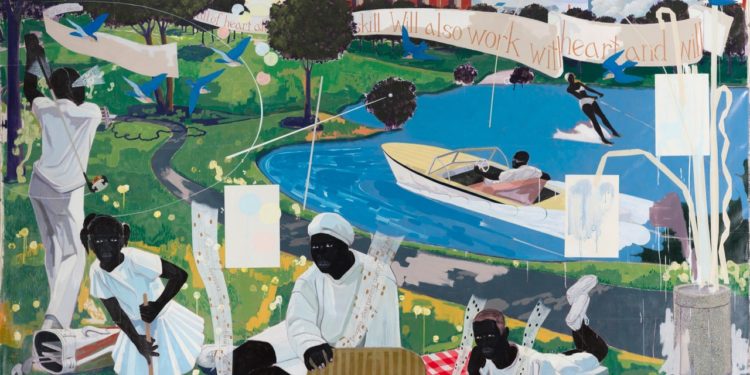

Painting after painting bore witness to the fusion of image and idea, and to the subtle, not so subtle, and sometimes hilarious references to art history. The “Vignette” series (2003-12) shows mostly young Black people in antique clothes enjoying the rococo charms of Fragonard’s “The Progress of Love.” “Do Black people seek out pleasure?” Marshall asked me. “Of course. So let’s have some of it.”

In “Black Painting,” whose blackness is so deep that it takes a minute or more to make out the image, two people are in bed, one of them a woman who has just heard something that prompts her to raise herself up on one arm. Marshall’s junior high school was a few blocks from the Black Panther headquarters in Los Angeles, and he remembers the police raid on it in 1969. His painting shows “the instant when nothing has happened yet, but it’s about to happen,” he said. “It’s not Fred Hampton and his wife; it’s meant to evoke the whole range of police raids on the Black Panthers.” The painting is dated 2003-06, because Marshall was not satisfied with its first incarnation; he took it back from his New York gallery and continued to work on it, off and on, for three years.

Marshall’s paintings often have inexplicable elements. “7am Sunday Morning”—the title refers to Edward Hopper’s “Early Sunday Morning”—is divided down the middle. The left half is a precise, almost photo-realist rendering of a street crossing near Marshall’s studio, with red brick storefronts, a pedestrian in a yellow jacket, and a flight of birds overhead. The only unclear object is a blurred gray car, speeding across the space and linking the left side of the painting to the right side, where nothing is clear. I asked Marshall what was going on there. “It’s like a lens flare,” he replied. “It’s the sun reflected in the glass of that building on the corner, an optical phenomenon that lets you introduce into the space something that’s not there, a mirage.” His aim was to catch “a moment that’s miraculous in the context of a mundane, ordinary day.” There are several such moments in his huge, 2012 “School of Beauty, School of Culture,” which channels his earlier “De Style” and also Velázquez’s “Las Meninas.” Here we are in a hairdressing salon, where eight or nine women talk or preen or stand and watch. The critic Peter Plagens described it as “one of the most complex orchestrations of color in contemporary painting.” A large poster of a woman with a flower in her hair, on the wall at the far right, is from Chris Ofili’s 2010 show at Tate Britain in London. (“I was absolutely floored when I saw that image,” Ofili told me. “I’m still honored when I think of it.”) Two toddlers are in the foreground, one of them a boy, who is peering at a distorted yellow-and-white shape on the floor, which no one else seems to have noticed; it is an image that can be seen only from an extreme angle, an anamorphosis, like the skull in Hans Holbein’s “The Ambassadors”—in Marshall’s painting, it is Walt Disney’s Sleeping Beauty. The idea of white female beauty as the impregnable standard in Western art is only one of the questions raised by this endlessly evocative painting.

Marshall’s craftsmanship and free-ranging imagination make his later work as unpredictable as “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self.” The “Painter” series shows confident, sumptuously dressed women and men, several of whom pose in front of their unfinished, paint-by-number canvases. Anyone can paint, they seem to say; their absurdly oversized palettes are abstract paintings in themselves. There is a series of imaginary portraits, most of them of historical figures such as Nat Turner, the rebel slave, who holds the hatchet he has used to kill his master, and Harriet Tubman, portrayed as a young woman, with the man she just married, who has vanished from the historical record. The exhibition at the Met also included an example of Marshall’s photographs of people—himself, his wife, and several close friends—in black light, which is ultraviolet light. “What this does is to give this beautiful dark tone to the skin, and a kind of blue wash over everything,” Naomi Beckwith, the Guggenheim Museum’s chief curator, and one of the sitters, said. “Kerry has always been interested in the question ‘What would art history look like if we had saturated it with Black American cultural history?’ ”

The most indelible painting in the show, to me, was his 2014 “Untitled: (Studio).” It shows four people and a yellow dog in a room where radiant color and magically calibrated design make it feel like the most desirable place on earth. It’s hard to imagine a painting more mysteriously seductive than this, but Chris Ofili is convinced that Marshall’s best work is yet to come. Comparing him recently to a Formula One racing driver, Ofili said, “For quite some years, we’ve been watching Kerry doing warmup laps to get his tires sticky. Now he’s ready to assert his authority on the contemporary history of painting. His tires are sticky, and he knows he can take the corners a little bit tighter than before.”

A big retrospective can derail an artist’s career, but Marshall took his in stride. When “Mastry” was about to close at the Met, the museum gave him an informal party in the Temple of Dendur which was one of the most joyous gatherings I have ever attended. Something magnificent had happened, and was being celebrated. Soon afterward, Marshall went to the opening in Los Angeles, and then returned, with a sigh of relief, to his studio and his unrelenting work schedule. Only a few people were aware that he had undergone successful surgery for prostate cancer early in 2016. In the past two years, Cheryl Bruce has had a pulmonary embolism and a second knee replacement. They are both in good health now, and they have decided to move to Los Angeles. It won’t happen for a few years—they are too busy with ongoing projects and obligations—but the bitterly cold Chicago winters and a yearning to spend more time with their families are too strong to resist. Marshall’s brothers and sisters and their children live in or near L.A., and so does Bruce’s married daughter, Sydney Kamlager, who went into politics and was recently elected to the California State Senate. (Marshall, her godfather as well as her stepfather, now calls her Senator Godchild.)

In the meantime, their Chicago life continues as before. Marshall gets up at five-thirty or six every morning and is in his studio by eight-thirty. Before her knee operation, Bruce was performing several times a week in “Theater for One,” a production, in Chicago, for a solo actor and a sole audience member. In the evening, Bruce cooks dinner, and they argue and spar amiably. She makes fun of his erudition, calls him El Jefe, and threatens to beat him up. Years ago, they had talked about having a child. “The timing was always wrong, and somehow it didn’t work out,” Bruce said. After dinner, they watch classic films from Marshall’s extensive collection, and at eleven-thirty they tune in to “NHK World-Japan,” a Japanese channel (in English) that Marshall, who discovered it, describes as being devoted to explaining what it means to be Japanese. “You see craft traditions that are hundreds and sometimes thousands of years old,” he said. Lately, they’ve been glued to the sumo-wrestling tournaments that are shown for fifteen days every other month. “Cheryl has become obsessed with sumo wrestling,” Marshall said.

Since his retrospective, the prices paid for Marshall’s work embarrass him. “Past Times” sold at Sotheby’s in 2018 for twenty-one million dollars, the highest auction price yet registered for a living African American artist. (The buyer was Sean Combs.) David Zwirner, the mega-dealer who represents Marshall in Europe, told me that his new paintings can sell for seven or eight million dollars. Marshall is a semi-celebrity: his name turns up in rap songs, including “Vendetta,” by Vic Mensa, and “One Way Flight,” by Benny the Butcher. He is working on a new series of paintings, called “Black and part Black Birds,” which will eventually include all the species in John James Audubon’s “The Birds of America” that are black or have black markings. Using Audubon’s images as a starting point, he depicts each species in a fanciful environment, perched on trees and posts adorned with brilliant flowers. Marshall is a longtime bird-watcher. A few years ago, he captured a juvenile crow in his bare hands—the bird was sitting on a low limb of a tree near his property, and he managed to sneak up on it from behind. He tied one of the bird’s legs to a milk crate on the second-floor deck of his house, took photos and videos, set out water and mulberries for it to eat, and released it the next morning. “I’d always had a fantasy about a crow that was my friend, and would come to my call,” he told me.

“London Bridge,” which he painted in 2017, is his most recent history picture in the grand manner. The famous landmark was judged unsafe for traffic in the early sixties, and an American entrepreneur named Robert P. McCulloch bought it from the city, dismantled it, and used the parts to create a replica, as a tourist attraction, on the shore of Arizona’s Lake Havasu. “The picture is about dislocation,” according to Marshall, who obviously had a fine time painting it. Among the tourists strolling near the bridge is a Black man, dressed in the Beefeater costume of the guards of the Tower of London. He’s wearing a sandwich board that advertises “Olaudah’s Fish and Chips,” which refers to another dislocation. “One of the earliest slave narratives was by Olaudah Equiano,” Marshall explained, smiling broadly. “He and his sister were sold into slavery as children, and Olaudah ended up as a servant to a British sea captain. He eventually became free, settled in England, married an Englishwoman, and got rich from his book.” In the painting, Marshall said, “the staff he carries has a picture of Queen Victoria, and the song he’s singing”—it’s notated on a scroll—“is the Rolling Stones’ ‘Sympathy for the Devil.’ ” The painting was bought by the Tate, where it quickly became a crowd favorite.

Marshall’s determination to know more than anyone else about whatever he does is unabated. “Kerry is like Goya, you know,” Madeleine Grynsztejn told me. “He’s a political, social, emotional, intellectual powerhouse.There’s a drawing that Goya made in his last years of an old man, bent over, leaning on two sticks, who says ‘Aun aprendo’—I’m still learning. That’s Kerry.” ♦

Credit: Source link