If “Matrix” were written by anyone else, it would be a hard sell. But Lauren Groff is one of the most beloved and critically acclaimed fiction writers in the country. And now that we’ve endured almost two years of quarantine and social distancing, her new novel about a 12th-century nunnery feels downright timely.

Still, a medieval abbess is a challenging heroine — living, as she does, a millennium away from us, suspended in that dim historical period long after the Romans but centuries before Shakespeare. We need a trusted guide, someone who can dramatize this remote period while making it somehow relevant to our own lives.

Groff is that guide largely because she knows what to leave out. Indeed, it’s breathtaking how little ink she spills on filling in historical context. Details about the court of King Henry II are omitted as though the Angevin Empire were as familiar to contemporary Americans as Westeros. What you might already know about Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Second Crusade — probably little — will not be much increased by reading “Matrix.” And though it covers more than 50 tumultuous years, this entire novel wraps up in the space it would take Ken Follett to warm a cauldron of gruel.

At the center of Groff’s story is Marie de France, a shadowy writer known today as the author of a series of courtly love poems. The rest of Marie’s biography is an open conjecture, and Groff rides into that lacuna on a noble steed.

Her Marie descends from a line of “loud opinionated unnatural women,” warriors in the Ladies’ Army during the Crusades. “A creature absent of beauty or even the smallest of feminine arts,” this Marie is “three heads too tall” with a shockingly low voice and massive hands. She’s also the product of rape, but she’s closely enough related to Queen Eleanor to receive at least a smidgen of royal patronage.

When “Matrix” opens, Marie, all of 17 years old, is appointed prioress of a dilapidated abbey, founded centuries earlier, where a few nuns remain scavenging for food. The beautiful queen, whom Marie adores, frames this assignment as a great honor, but the young woman knows she’s “being thrown away like rubbish … sent into her living death alone.” Indeed, there’s a whiff of Edgar Allan Poe as Marie approaches this “dark and strange and piteous place” surrounded by fresh graves. She’s greeted by two derelict nuns — one mad, the other angry. She dismounts and falls into a pile of manure.

Things go downhill from there.

Marie finds the accommodations primitive, the food repulsive, the domestic and prayerful duties stultifying. “The nun’s life seems as bad as she thought it would be,” Groff writes.

“She thinks of running away from the abbey; of running into the woods alone and catching beasts to eat with her hands and drinking from the freshets, becoming a wildwoman or a lady brigand or a hermit in a hollowed trunk of a tree. But even on this island there are few wild places left, no place that did not at last end up too close to a village with other humans in it. No, she is caught in a great net made by her sex.”

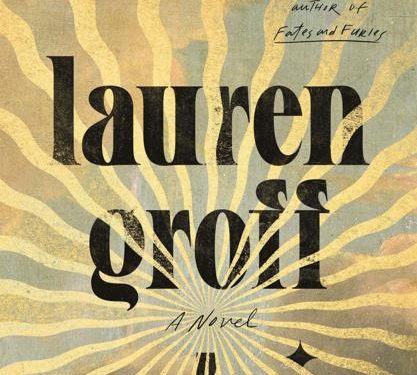

In the end, Marie is a warrior, not a quitter. Though “Matrix” is radically different from Groff’s masterpiece, “Fates and Furies,” it is, once again, the story of a woman redefining both the possibilities of her life and the bounds of her realm. Unable to leave and unwilling to fail, Marie brings her considerable physical and mental powers to bear on the abbey’s financial and managerial problems. The sisters — most of them, anyway — grudgingly come round to her wisdom because, although she feels no particular spiritual motivation, she’s wholly dedicated to their work.

One of the novel’s most curious elements is the way Marie’s labor accrues a kind of holiness that redounds to her in startling visions. The authenticity of her sightings of the Virgin remains ambiguous, but there’s no doubting her determination to create a sanctuary for women beyond the reach of men. It’s an audacious goal, particularly within a political and ecclesiastical organization predicated on the superiority of men. But Marie becomes dazzlingly adept at using the elements of repression to her own advantage. In her most provocative move, around the abbey she engineers a vast labyrinth, a structure whose devotional aura almost camouflages its defensive function.

That’s a strategy Marie will pursue again and again as she struggles to transform this once impoverished abbey into a female oasis. And inevitably, her efforts will conflict with the masculine tropes and rituals embedded in the Roman Catholic faith. How far she can push back against that outer world without provoking forces arrayed against her generates much of the novel’s suspense.

Almost a decade ago, in a gorgeous novel called “Arcadia,” Groff explored the inevitable failure of a commune in Upstate New York. But given the multiple shocks of the past few years, the utopian impulse that once felt so tragic and nostalgic suddenly looks curiously viable — even translated into the alien world of 12th-century monasticism. Although there are no clunky contemporary allusions in “Matrix,” it seems clear that Groff is using this ancient story as a way of reflecting on how women might survive and thrive in a culture increasingly violent and irrational. The costs and sacrifices are high, but on a planet grown “too hot to bear humanity,” who isn’t tempted to have faith in the possibilities of a small society of like-minded believers walled off from the flames?

Credit: Source link