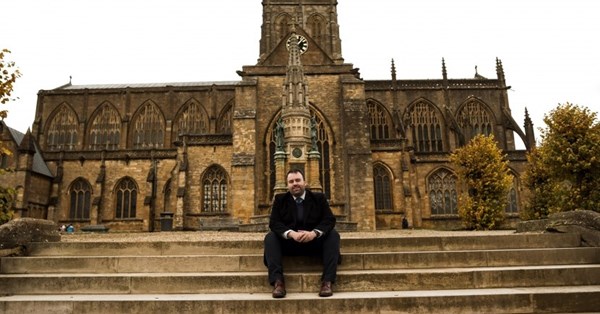

THE morning before my first day in Parliament, I went to church in Sherborne Abbey — my spiritual home. I was moved when prayers were read for our new Government and for Parliament, as it is not often that you receive prayer in that way. It was a special moment, and one that strengthened a bond with me and my Church and my faith.

But, within months, I found myself wrestling with a situation that I never thought I would see: churches being closed not only to parishioners, but also to clergy — a decision that, I believed, pushed the boundaries of the law (News, 27 March 2020). An incumbent has the legal right to enter their church, but clergy were put between that rock and the hard place of canonical obedience, with threats of disciplinary action from their bishop if they entered their church.

Down here in Dorset and Somerset, as indeed in other parts of the country, we had countless direct cremations (cremations with no committal or service), partly because the Archbishops maintained their position of no funerals in church, some crematoria followed suit for the sake of it, and some said that they could not cope with the additional numbers from closed churches.

I challenged the Secretary of State in the House of Commons about this. But he told me that it was not the law of the land, but the diktat of the Church. Weeks later, the Prime Minister confirmed the same to the Father of the House, during a call with concerned MPs.

It put parish clergy in an awful position. It pushed members of the community away from their cherished churches when they needed them most, and, on Easter Day in 2020, the only communication you could have was via a priest’s dining room or the Archbishop’s kitchen; so, I listened for the Sanctus bell of my local Roman Catholic church, and watched the Pope from St Peter’s, Rome, instead.

I prayed about what I could do about this. I thought, in this “secular world”, that Parliament wouldn’t take much interest. But what happened subsequently was a real surprise: almost 40 MPs responded to my note asking for their support; and we subsequently wrote to the Bishops to express our views on this matter, which created quite a storm (News, 8 May 2020). Some bishops were very grumpy indeed, not to mention Lambeth Palace.

THIS shows that, despite what people may think, Parliament is, I believe, the most Christian that we have seen for a very long time. There is growing appreciation of the Established Church and the part that it plays in society.

Parliament sees these things much more clearly than it has for a very long time: that the Church of England should be politically neutral, so that it can bring people together through what they have in common rather than entrench what divides them; that bishops should challenge and express their Christian viewpoint to politicians, but they should not favour one group of a community over the other because of a political viewpoint — unlike the disgraceful Bishop of St Davids (who should resign) (News, 11 June); that the parish is the linchpin of kindness, community, and mutual support, and the walls of parish churches hold within them centuries of our family and community history to learn from; and that parish churches are the custodians of our sadnesses and our joys, which are shared in prayer with God.

The Second Estates Church Commissioner used to have to encourage people to ask him questions in the House for Church Questions. Now, there are so many, you are lucky to get a slot.

There are so many of us who now go to church that it is clear that the December 2019 General Election did not just change the political make-up of the Commons: it changed its faith make-up, too. I am not the only churchwarden who is an MP. Theology graduates are now on the back benches. Groups of us go to worship together. We go on pilgrimage together. We have a Church of England WhatsApp group, with dozens of MPs. And, in case you’re wondering, I’m talking about Conservative MPs, not the Opposition.

IT IS not well known enough that the General Synod is a delegated body of Parliament. In respect of the law, it has similar powers to a government department, and, when it wants to change the law, it lays those changes, normally through statutory instruments, before the Commons, via the Ecclesiastical Committee. They will become law unless Parliament “prays” against them.

The Early Day Motion that has been tabled in the Commons, “praying” that legislation passed by the Synod to reform the Church Commissioners’ governance be annulled (News, 10 September), shows that Parliament has a renewed interest in the Church of England.

The main difference, though, is that, while the hierarchy of the Church grandstand their political views to journalists rather than speak about their genuine concerns with elected politicians, MPs are now looking at the Church of England to make sure that it serves its purpose to support communities across the country, and that parish ministry and clergy are valued much more than a bloated woke bureaucracy that abstracts money and power from the front line and pretends to be something that it is not.

Chris Loder is the Conservative MP for West Dorset.

Credit: Source link