Americans adopting children from India is not new. In 2021, India sent 245 children, the second largest after Colombia, for adoption, according to data released by the U.S. State Department. However, there is little research done on the lifelong impact of the adoption experience on the adoptees, especially in the adolescent years, and their families. Studies suggest that essential shifts in life roles and relationships occur in the post-high school period. In early adulthood, when the adoptees analyze their roots and belonging, it may trigger insecurities about their identity and self-worth.

In the adoption triad, there is the birth mother/family, child, and adoptive parents. Birth mothers and their families are constantly ignored or spoken of negatively in society. The adoptees, biologically separated from their mothers, are traumatized and yearn for love and a sense of belonging. The adoptive parents are often the voices one hears the most. Adoptees’ voices are not often heard.

It is, however, crucial to listen to their lived experiences. I have collected the life experiences of a few Indian adoptees who came to the U.S. in the 1980s and were mostly raised in small rural towns. I will focus on their self-identity and their identification shaped by myriad life experiences growing up in ‘foreign’ families vastly different from their roots. It is not only race and ethnicity that separates them, it is also their cultural backgrounds — language, religion, food, attire, and customs. Being separated from their birth families at a very young age, these children have tried to cope with racial and cultural differences. They have come a long way in making a space for themselves, shaping their careers, and building their families.

Transracial Adoption: A Few Case Studies

Leela Black, 41, lives in Portland, Oregon. A premature baby born in Kolkata, she was adopted by a single mother from Oregon on Sept. 18, 1982, when she was two months old. At the time, Leela was malnourished and was diagnosed with hearing loss and cerebral palsy. Her adopted mother was a pediatric nurse, and the first five years of her life were devoted to speech, physical and occupational therapy, and hearing resources.

Leela is now married with two children — a 9-year-old daughter, and a 5-year-old son. With a Master’s in Rehabilitation and Social work, she works for the state of Oregon to provide accommodation and livelihood to the marginalized.

Growing up in a White family, Leela became aware of her color difference very early, and her adoption was always part of family discussions. Her mother, however, did expose her to all things Indian, including music, dance, and plays. At age five, she remembers eating Indian food for the first time and loving the spicy food.

Leela’s journey as an adoptee has not been easy. A part of her is very thankful that her mother adopted her. In India, with her health condition, she would have died. When she was in seventh grade, her mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder after a car accident. She remembers her mother yelling at her, without knowing why. “It was not easy in high school to grow up with a bipolar mom.” She learned to cope with her mother’s disorder by staying focused on her studies. She learned to grow up fast for her mother, and family, and also to hide her pain and keep a happy face. At the back of her mind, however, she always thought about her roots and her birth mother.

In 2018, her mother was diagnosed with a severe condition of dementia. Three years later, in 2021, having moved her to a local assisted living facility, Leela’s life journey has come full circle. She visits her four times a week as her sole caretaker.

Leela identifies as an East Indian. In college, she was close to her roommate, who was also adopted from the same Kolkata orphanage. They watched tons of Bollywood films, learned to cook Indian food, and went to Indian get-togethers for Holi and Diwali.

She has been to India thrice. Before marrying her white American boyfriend, she took him to India. “I did not want to marry somebody who had never been to India.”

In 2014, Leela did a DNA test and found a few biological cousins in Minnesota. She is close to one of them, who looks like her, even though they are fourth cousins. She also finds solace in connecting with the adoptees from India. In 2018, she started the East Indian Adoptees of Oregon/SW Washington Facebook group and has planned numerous activities.

Highest Sense of Right

Ian Forber-Pratt, 43, is the deputy executive director at the Children’s Emergency Relief (CERI) in St. Louis, Missouri, and leads in the field of global child protection and childcare system reform. He is married to a Muslim from India, and they have two biological children, 5 and 1.

On Aug. 27, 1980, Ian was born prematurely with low birth weight at Sri Krishna Nursing home in Kolkata and subsequently brought to the International Mission of Hope (IMH), an orphanage in the City of Joy. At two months, he was transported to Natick, Massachusetts, to be with his adoptive White parents.

From very early on, Ian stood out because of his race. He remembers how in kindergarten, friends asked him why his mother and father were White. He was the first child of his parents, devout Christian Science practitioners, who were making their “highest sense of right” in adopting him and his sister. Ian’s mother was a Christian Science nurse and later a 5th-grade math and science teacher; his father is a CPA. His sister Anjali, who joined them later, was born in Kolkata in 1984. After adopting Ian and Anjali, their parents also had two biological children, Henry and Wendy.

Ian says that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, some people saw adoption as a way to expand the community’s view of the world and serve those in need. “Altruistic and often good in intent, many adoptees ended up in families that were performative rather than organic.”

Early on, Ian was ignorant of his Indian identity; growing up in a White household, he deeply desired to assimilate into mainstream society. His Indian identity confused him as well. He often wondered if he was “abandoned.”

At age 15, Ian joined Principia, a Christian Science private college-prep school in St. Louis. In college, he experienced setbacks with addictions — smoking and drinking. He associates his addiction with his struggle for identity, the pain of not knowing anything about his birth mother, not being as good as a White American, the sudden loss of a friend, and having bad peer influence.

The study “Reclaiming Culture: Reculturation of Transracial and International Adoptees” by Amanda L. Baden, Lisa M. Treweeke, and Muninder K. Ahluwalia, suggests that going to college is a significant life event and may trigger transracial adoptees to doubt their sense of self, create a desire to learn about their birth culture, or inspire a search for their birth family.

Adopted as an infant, the only information Ian had from Shri Krishna Nursing home is that his mother was unwed. There were no details on his father. His research led him to find that in 2016, this nursing home was involved in the baby-sale racket. Although he may never know the situation surrounding his origins, he wonders what happened. Despite a wonderful life, loving parents, a beautiful family, and work, Ian says he “still struggles with anxiety, coping, and addiction, all of which are rooted in my origin story.”

Ian traveled to India in 2006, before living there for eight years. Being an adoptee, he realized the value of biological family and has worked extensively in India’s foster care system. He helped with a substantial legislative change in India as the country has moved from the large institutionalization of children to a wide range of family-based care. With the trauma he has carried all his life, he is deeply concerned about the traditional pathway of adoption followed in the 1980s — remove children from drama, provide the basics like housing and food, and send them on their way to adoption successfully. In reality, it leaves a significant risk for child trafficking.

Your Mother was Unwed

Tasha Sharmila (Roeloffs) Waggoner lives on her parent’s cattle ranch in the small town of Ruch, Oregon. She has worked as an aesthetician, is married, and has a 15-year-old biological son. Her spouse is a White, Christian, and a critical care flight paramedic for a nonprofit company.

Tasha was born in July 1982 at Shree Krishna Nursing Home in Kolkata, and at six weeks, she was brought to her Dutch parents in Oregon, who owned a cattle ranch and a diary. She was the only one adopted among three biological siblings.

Besides the color, Tasha quickly realized the many differences between her and her siblings. They were competitive bike riders, and good at riding a tractor, while for her, anything to do with the farm was not her thing. “They call me the ‘farm girl in stilettos,’ because I would rather be dressed up fancy and enjoy dancing instead of wearing my cowboy boots.”

Her most significant conflict within was not looking like anyone in her family. She remembers being called the “N” word in high school. However, her parents were supportive.“They have always told me that it is other people’s fault for being mean. They would remind me to pray for them.”

Tasha was raised as a conservative Christian and went to a private Christian school. She assimilated into the White culture and was socially popular — a top cheerleader in high school. At 18, however, she suffered from mental stress and trauma — bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder.

She always wondered about having no record of her biological family. All that her parents told her was that her mother was unwed and that they didn’t know her birthday. She always wondered what brought her to the U.S. and if she had any siblings. She heard from Children of International Mission of Hope, a Facebook group, that her orphanage was involved in child trafficking. It made her want answers. She was in a negative head space about it for years.

She went through counseling and is still searching for an answer. Her counselors confirmed that childhood trauma was responsible for her bad decisions in relationships and her anxiety and stress. “If I had not gone through counseling, I would still think about it and still struggle and wonder why.”

An Urge to Go Back

Anjali Dreyer is 33. She works as a district manager for a beauty company in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She grew up at the Green House orphanage, the Welfare Society of Patna. In 1991, at age 3, Anjali remembers “getting off a plane with tons of flashes from cameras and people grabbing me when I arrived at the Minneapolis/St. Paul airport.” She came home with four other girls. “It was a traumatic experience.” She was frightened and felt lost. At the time she had a chronic hepatitis B problem.

Anjali, who was raised in her adoptive parent’s Lutheran religion, says it was a big adjustment when she first came to Des Moines. She did not speak for a year as she was trying to learn English. “My parent’s friends spoke to me in Hindi over the phone and would comfort me, making sure I understood what was happening.” She does not have pleasant memories of the Indian orphanage where she spent her first years. However, she vividly remembers the surroundings and the Ganges river, where she spent her early childhood.

Anjali’s sister, five years older, was adopted from Bangalore at five months. Both their experiences were very different. They moved from Des Moines, Iowa, to Sauk Rapids, Minnesota, a tiny town when Anjali was six. Her sister was in middle school and tried to fit into the mainstream culture.

She was “the only dark-skinned person” in her grade, and “wanted to cling to Indian culture.” She wore salwar suits, watched Bollywood films, and tried to learn Urdu and Hindi. That was her way of finding roots, her connection to her birth parents, and her culture. She spoke Hindi but gradually lost it without practice and the pressure to speak English as her first language. Anjali misses the language, music, artwork, and history of Indian culture.

Even though her parents were very loving and supportive, the cultural environment was hostile. Growing up in a small town, she experienced micro-aggression and flat-out racism in school through her teachers and peers.

At the age of 12, Anjali got the opportunity to return to India to help her mother escort an adopted baby. “I always had memories and an urge to go back,” she says. She visited orphanages, some villages, and surrounding forests which deeply impacted her. Anjali says it is essential to facilitate adoptees’ to connect to their country of origin. Adoption agencies only sometimes favor children or adult adoptees to stay connected to their roots.

In that trip, Anjali saw India “not as a typical tourist.” She learned “a lot about what it would be like to live in an orphanage,” which is “not a home and not a place for a child to grow up in and develop.” She feels that had she continued to stay in India and not come to the U.S., “it would have intensified feelings of abandonment and feeling unloved. I’ve been able to grow up (in America) feeling loved and know I’m surrounded by a supportive family.”

When Anjali joined St. Cloud State University, Minnesota, she joined the Indian Heritage Club on campus. She was thrilled to have South Asian women mentors who helped her appreciate her looks, hair, and persona. At 18, her parents supported her in getting her an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) card. She feels she did not have to ask to go to a country that was her birthright.

After college, she moved to the Twin Cities. Being in a diverse city helped her to meet other South Asian women co-workers who became her family. She celebrated festivals like Diwali and Holi and was able to go to cooking events and Indian weddings.

Is it a Rescue of Disadvantaged Children?

The social expectation is that adoptees should always be grateful for their adoption – ignoring that it is a complicated, lifelong, and often traumatic journey – and more than just a “happy one-time event.” Anjali says adoption gets the hype as an excellent service on the part of American parents rescuing Indian kids in poverty. “My parents were glorified for adopting, and I was expected to be grateful and relieved.”

In reality, there is a lot of grief, pain, and suffering. The child is forced to take up a new identity, lose their birth name, language, culture, and even medical record, and is expected to erase the past as a norm. Anjali says it is high time the adoption description and process changed, with more voice for adult adoptees. Unfairly, the adoption agency gets the credit for the whole process.

“We hear from others that you are wonderful, like Mother Teresa, and that the kids should be grateful,” says Judi Kloper, an adoptive parent of three kids from India. American society expects the child to be better off being here than in their own culture with their birth family. Many kids whose adoptive families did not connect with their children have struggled. There are many sad stories out there.

Blonde Hair and Blue Eyes

Nandeeta Ramsey has lived with stress and anxiety and never felt like herself in her 35 years of adoption. She is an international adoptee born in Kolkata and raised in Oregon. Now she works and lives in Corvallis, Oregon. As per the adoption documentation, she was born on April 28, 1988, weighing 3 pounds, 1 ounce. She was in an incubator for the first few months of her life. At seven months, in November 1988, she was flown to Portland for adoption.

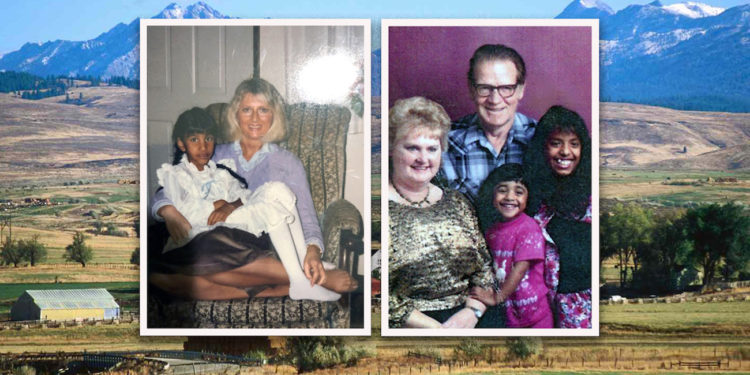

Her birth name in India was Parineeta. Her adoptive parents, Jo and Larry Ramsey, changed it to Nandeeta. They were older, and worked in the military — her mother, a registered nurse, was in her 40s, and her dad was in his 50s. Her mother could not have children of her own; they had already adopted Mala from the same orphanage, nine years older than Nandeeta. When Jo adopted Mala, she was in her mid-30s. She then met Larry. They got married, and then adopted Nandeeta about eight years later.

Nandeeta grew up with her family in Jefferson, Oregon, a rural conservative town. They lived in the country and hardly had any social life. She remembers bonding with her dog, who followed her everywhere. Half of her town’s population was White, and the other half was of Hispanic/Latin descent. Besides her and Mala, one other male adoptee was from India. The three of them constituted the total Indian population in the town.

Reflecting on her tragic loss, starting with her birth certificate, she notes how the adoptees don’t have access to their original birth certificates. “My birth certificate has my adoptive parents’ names and the country I was born. It does not have my birth parents’ names.” International adoptees’ original birth certificates are sealed in America.

The racial difference between her and her parents was stark, she observes. With her mother’s blonde hair and blue eyes and dad’s dark reddish hair and blue eyes, she knew this was not her family; she was not in the right place. She grew up scared and just wanted her mother to love her. However, her parents expected her to be grateful. “If I was upset or angry, I could not express that. I would get into trouble.”

As their mother usually worked at night, Mala became a caretaker for Nandeeta, and they became close. When she turned 9 and was in fourth grade, Mala turned 18 and graduated from high school. She left for Southern Oregon to be with her boyfriend, to whom she got married later, and had three children. With Mala gone, Nandeeta felt abandoned. She was never close to her adoptive mother but had a special bond with her father.

So, at 19, she was devastated when her father passed away, and she took herself down a spiral of self-destruction through drinking. “I drank because of my painful adoption and then the loss of my dad,” she says. “My mom and I tried to work on our relationship, but it was challenging.” She says 50 percent of adoptees 35 and older are estranged from one parent or both. Many adoptees share their stories and are open about their thoughts on this topic, and many others do not speak up due to fear, obligation, or guilt.

She also self-harmed for years, starting as a teenager. She would run her hands under hot water. “It is a pain I can tolerate because I cannot take the emotional pain. She attempted suicide in January 2021.

Lina Vanegas, in her article “Demystifying the stigmatization of adoptee suicide,” says adoptees are four times more likely to attempt suicide, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics report 2013.

After a long bout of drinking, she takes great pride that she has been sober for the last 9 years. She has been part of many global, national, and regional organizations promoting the interests of the adoptees, organizing them, and creating a collective voice for them. She is against adoption. “It is human trafficking,” she says. “As an international adoptee removed from my biological roots, racial mirrors, native language, culture, and home country, to be placed in America as a pawn in the human trafficking circle is sick.”

She wonders why adoption is painted as such a noble job on the part of the adoptive parents. It is treated as beautiful and life-saving; the adoptee should show gratitude regardless of their tumultuous loss. Instead, adoption begins with trauma and loss. Every year her birthday is a dark and painful day. She says there is nothing beautiful about breaking families apart.

While she feels fortunate compared to her peers in India, she points out how she needs to be grateful for the better life she has here, as she was “chosen.” This illustrates how “religion and adoption go hand in hand,” she says. “I hate religion because of my adoption and I hate adoption partly because of religion,” she adds. “Materialistically I may have been more fortunate, but I was emotionally, mentally, and physically bankrupt. I lived in survivor mode. No person, let alone a child should have to take that on for decades.”

A painful aspect of transracial adoptees’ identity development is that they are expected to fit into and accept their new White family. In their 2013 book, “Inside Transracial Adoption,” Beth Hall and Gail Steinberg say that since transracial families are visible, it is impossible to hide the physical differences between parent and child, automatically inviting unwanted attention and intrusive questioning from acquaintances and strangers.

While everyone struggles with their identity at some point, transracial adoptees face additional challenges. They can become preoccupied with their adoption, grappling with missing or complex information about their past and questioning their familial loyalties — something adoptees I spoke with agreed.

Feeling of Loss is Always There

Forty-three-year-old Alexis Jackson is a college graduate and a professional working at Nike Marketing Operations in Portland. She identifies as an adoptee, American, Indian, Brown, and a woman of color. She grew up as an Episcopalian and is married with three biological kids.

Alexis was born in Kolkata in 1979 and, at the age of 4 months, was brought to Oregon for adoption. She came home to mom, dad, big brother (eight years older), grandmas, and many aunts and uncles. Her parents had a deep commitment to adoption, and eventually, her mom and stepfather founded Journeys of the Heart Adoption Services, where her father joined their business and worked with them until the company closed in 2019. Her parents adopted two children after her. Lily, 10 years younger, is from China and her brother Tino, 15 years younger, is from Romania.

She is very close to her parents and younger siblings. She now lives next to her aging mother and stepdad to help them, and her children benefit from being close to their grandparents.

Alexis says the deep feeling of loss and abandonment as core issues of adoption for many adoptees has been tremendous and, unfortunately, is a continuous process of coping with grief. She grieves the passing of her adoptive father in 2020.

Alexis is the only Brown person and Indian adoptee in her family. Growing up in a White community with White family members, she realized that she was “the only Brown kid” and “did not have the same White privilege as my parents, and that was a hard and sad reality.” She did not have any exposure to Indian culture. “If my parents took the plunge and got me to India in early, mid-childhood and teen years, providing me with the opportunity to learn a language and have the language awareness and immersion would have been tremendous.”

Her neighborhood was very White, and she saw other Indian adoptees only a few times a year. She was in a White school till the age of 12. She suffered intense loss and pain. When her counselor looked deep into her past and asked about her feelings about being Brown, her birth mother, and her Indian identity, Alexis realized she was hurting. She wanted to know where she came from, the circumstances that led to her adoption, and her birth mother. The open-ended conversation became a grieving process for her loss.

In sixth grade, she insisted on joining a Catholic school to experience diversity. At school, she started building a community of her kind. “I knew I was not the only kid of color. I started building a safe space where we could understand and talk about our experiences.”

At college, she thrived on diversity. All her friends in college who are still in her life today are people of color. At work, in Nike corporate world, with Michael Jordan as the head, she has developed deep-rooted connections with many people of color and the Black community.

Alexis went to India at the age of 20 and 21 while in college and lived there for some time. She returned to the Kolkata orphanage and connected with a nurse who claimed she had taken care of her before adoption. It gave her a deep connection, even without any information about her birth. The India experience was tremendous. “The racial awareness and cultural understanding provided self-esteem in my 20s that was imperative to my development as a young adult. I understood where I came from, felt the loss, and the reconciliation of many of the core ‘issues’ of adoption.”

As an adoptee of color with Indian roots, Alexis says adjusting to the world is the greatest challenge for people of color and, undoubtedly, Brown/Black women. “How we give and provide a foundation of racial/culture to our children is an incredible challenge, especially for those raising children in non-diverse states/cities/towns.”

She says her most significant challenge is raising biracial children in Portland. Her daughter is learning Indian dance and is in more diverse schools. She found (pre-pandemic) that corporate Asian networks are a great way to find community and build connections.

Mary and Bryan: Orphans in Love

Mary Evans lives in Portland and works as a social worker in the city’s public schools. As an infant, she came from the IMH orphanage in Kolkata, being adopted by a single woman, a registered psychiatric nurse working in mental health facilities, residential facilities, and children’s hospitals. She grew up with her mother, aunt, a biological cousin (her aunt’s daughter), and nine adopted kids in the same house. She remembers her home as open and welcoming. But in inner northeast Portland, where she grew up, there were hardly any Indian Americans.

Mary loved Indian food — from as early as age five or six, she explored and savored different Indian restaurants in Portland as opposed to her mother, who found the food too spicy. She enjoyed Indian costumes — her mother’s Indian coworker brought them for her, some she still has. She treasured the potlucks the adoption agency hosted for Indian adoptees and their families.

Mary has not been back to India. But she married Bryan, an Indian adoptee from the same orphanage in Kolkata. He was born in 1986, and at the age of 3 months, he came to California. She met him through a Facebook group of adoptees from the IMH orphanage.

Bryan grew up in a rural conservative town in California. He was the only adoptee in his family and had no exposure to Indian culture while growing up. “I was the only person of color in my entire school for most of my life, with maybe one or two Latino or Black children,” he says. “For the most part, it was just me. Very different.” When he was 5 or 6, his mother took him to the Indian heritage camp in Colorado, and he instantly fell in love with the Indian culture and the people he met there. He attended it several times during his school years. His stepfather is also Indian.

In 2021, Mary and Bryan celebrated their marriage with both of their sons. They wore Indian costumes and served Indian food to 150 guests. Mary, being raised Catholic, took pieces of Indian and American cultures and combined them in a way that was respectful of what they wanted to be included.

Mary and Bryan have two boys, Ravi, 10, and Rohan, 5, who are drawn to Indian culture. They admire India because it is their parent’s birthplace. Mary and Bryan are proud of their Indian heritage and want to educate their children and learn together. The children are learning about the Hindu religion and Indian feasts and festivals like Diwali and Dussehra in a more diverse environment. Teachers are incorporating Indian culture into their education as well.

Mary and Bryan are part of the adoptee network in Portland. They are one of the very few who have an unspoken common ground of where they came from, and they do not have to explain not knowing their biological families. They are raising their kids in America with exposure to Indian food, sports, and television. Mary has been helping the Indian adoptees to build relationships with groups of people.

Conclusion

All the adoptees I interviewed grew up in white families and experienced minority status in the family and community, more evident in the rural areas in the 1980s. “Many of these young people have felt othered as people of color. Many times, it comes from the environment, not necessarily the parents,” says Ian Forber Pratt. The rural white environment, homogenous schools, and environmental access are unequal.

As a minority, some adoptees have assimilated into their adoptive families’ culture and have created a sense of belonging. Tasha Waggoner realized that she was molded to fit into mainstream society consciously or unconsciously by her parents and grandparents. She was worried that her family would not accept her for who she was. “In 2017, my grandpa passed away, and my dad came to me and apologized,” she recalls. He cried and said, “If we could have done things differently, we would have allowed you to do the things you loved.” Tasha says she wanted “to be accepted by my family.”

Studies suggest that the White population in the United States tends to experience and view life through a lens of particular privilege. It can be challenging for White adoptive parents to recognize that the racial and ethnic differences between them and their children are essential.

Leela Black says the adoption should take place for the right reasons. The parents must do their homework, take classes, interview different adoption agencies, and learn about the culture which they are adopting a child from. They must have a psychological assessment of whether they can raise a child as well.

Many adoptees say that one major issue in transnational adoption is how to thoroughly vet adoptive parents and their point of view on race. Their point of view on race, education, and awareness and how they handle racial issues is essential to assess to see if they are “fit” to raise transracial adoptees.

Alexis Jackson grew up with very supportive parents, but unlike her younger siblings, who went back to their birth countries and are in touch with their birth families, she does not have that access. She says she has learned to live with the loss from deep within. It is a sense of inadequacy, constantly questioning and not being secure and feeling adequate.

For education and awareness about adoptees in the United States, Alexis has taught many pre-adoption classes to adoptive parents. She believes these insights, stories, and feelings shared in classes and interviews have tremendously impacted adoptive parents and adoptees.

Adoptees have started their initiative to support one another in a similar situation. The Indian adoptees growing up as a minority in diverse families in white culture have a shared uprootedness of being abandoned by the birth mother and the yearning to connect with people like them. They stay connected as Indian adoptees, the warm embrace and recognition of a shared experience, no matter how different their lives might be.

I am indebted to Judi Kloper, an adoptive mother of five kids, three adopted from India, who introduced me to all the adoptees in this story and inspired me to write from the adoptee’s perspective.

Annapurna Devi Pandey teaches Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She holds a Ph.D. in sociology from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and was a postdoctoral fellow in social anthropology at Cambridge University, the U.K. Her current research interests include diaspora studies, South Asian religions, and immigrant women’s identity-making in the diaspora in California. In 2017-18 she received a Fulbright scholarship for fieldwork in India. Dr. Pandey is also an accomplished documentary filmmaker. Her 2018 award-winning documentary “Road to Zuni,” dealt with the importance of oral traditions among Native Americans.

Credit: Source link