Man’s purpose in life is to know, love, and serve God with all of his mind, heart, and strength. This succinct answer to the world’s most vexed question holds compelling poetic beauty. Its strong, rhythmic monosyllables are like the rap of a snare drum which steadies troops in the face of battle.

Yet, one wonders, what actually is its implementation? How does one know, love, and serve God? And how does one really give all?

While reading Peter Kwasniewski’s recently published The Once and Future Roman Rite, the answer appeared to me as quite simple: To fulfill his purpose in life, man need look no further than the liturgy. The liturgy is the environment par excellence in which man may seek to know, love, and serve God with every fiber of his being.

But if man’s ultimate fulfillment is found in the liturgy, then it stands to reason that the form of that liturgy is of crucial importance. Kwasniewski writes:

The essence of the Church’s liturgy is simple: it is contained in the temple of the Heart of Christ, our Eternal High Priest, where perfect worship of the Father in the Spirit resides. But the “clothing” of that worship is of decisive importance to us, who interact with Our Lord through His visible Body, the Church, and through her visible rites. How these rites are structured, performed, and participated in will inevitably influence our understanding of the mysteries of the Faith and our ability to live them out (12).

In his first chapter, Kwasniewski compellingly discloses the role of tradition in nurturing the sacred rites, sanctifying man, and ultimately glorifying God. He refutes the objection that only validity matters with an insightful analysis of substance and accident. “I am aware of only one instance where, by divine power, substance is separated from accident,” he writes, “namely, in the miracle of transubstantiation,” and then goes on to explain that the substance of the liturgy is inextricably bound to its accidents, thus making the accidents (over which the Church has dominion) of vital importance (17).

Later, Kwasniewski links this analysis to his discussion of tradition’s beauty:

Beauty happens, so to speak, where there is a clarity about what the thing itself is. When someone is attracted to the traditional liturgy for its sights and sounds, it is not because he is stuck on these things but because these things coalesce around the reality, the Sacrifice of the Cross, and make it stand forth with a satisfying clarity. The surface qualities (or “accidents”) so harmonize with the nature of the mystery that the result is the splendor of the truth (25).

Kwasniewski has uncovered a subtle but crucial reality often overlooked by even the most erudite, namely, the sublime harmony produced by the union of the metaphysical beauty of the Cross and the physical (sense-perceived) beauty of the sacred rites. Scoffers dismiss the importance of this harmony or, like the tone deaf, deny its existence altogether; for them, the traditional liturgy is nothing but a show of smells and bells, a distraction, an embarrassing and irrelevant display. In the words of the Psalmist, such critics “have ears but do not hear.” Kwasniewski’s illuminating defense of liturgical beauty in the physical realm not as a mere aesthetic pleasure, but as an indispensable (and inextricable) accident to the substance of the reality itself, comes as a stroke of pedagogical genius and vindicates the multitude of faithful who have heard this harmony with the ears of their own hearts and sought to promote and defend it.

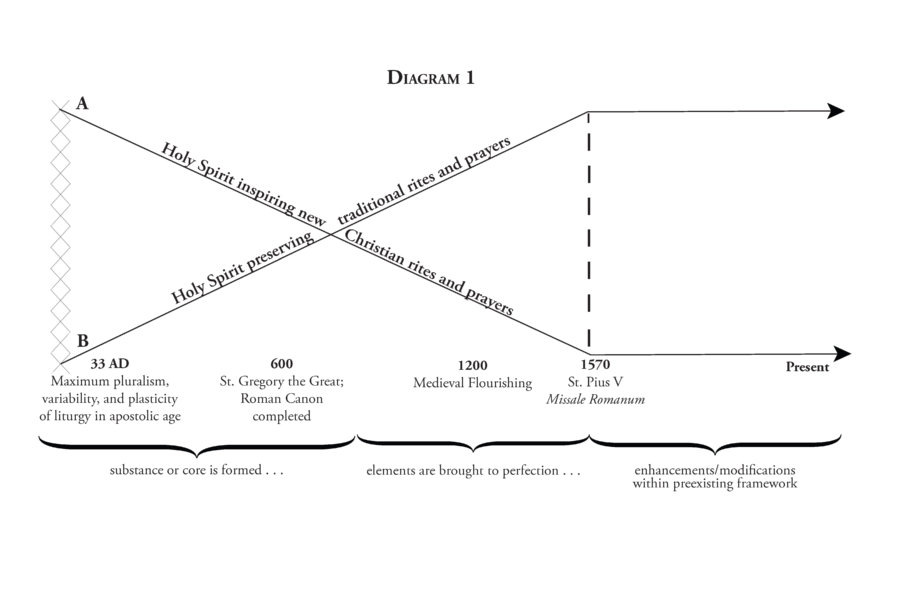

One may still wonder, though, where the traditional liturgy comes from, and what exactly differentiates its genesis from the rites which appeared following the Second Vatican Council. In his second chapter, Kwasniewski provides a wide historical and theological account of what organic development really means, and he formulates concrete laws of organic development based on his vast knowledge of traditional rites both Eastern and Western. Perhaps the most helpful portion in this chapter is his explanation of the rate of change in liturgical development and how it has varied over the ages. Kwasniewski’s insights dispel myths and misconceptions of antiquarians and Modernists alike.

Other chapters address, from various angles, what it means to say that a rite is “traditional” (or not), and what is really required if one is dealing with the Roman rite, as distinguished from many other Christian rites. He resoundingly argues that the Novus Ordo is not and cannot be considered the Roman rite—it is a new rite altogether, built out of manipulated and transformed elements from the Roman rite and much new material—and that, in fact, the Roman rite has more in common with the Byzantine liturgy than it has with the Novus Ordo. This claim may seem surprising to some, but Kwasniewski’s arguments are detailed and convincing.

The book’s final and most fascinating chapter contains a mini-dissertation on the changes made to Holy Week in 1955 as well as many other seemingly small but critical changes that occurred in the missal after World War II as the future architects of the 1969 missal warmed up to their work. After reading this chapter, one can have no doubt about the designs of the Second Vatican Council’s key liturgical players, and one realizes the inanity of clinging to a placeholder missal (namely, the one promulgated in 1962) which was at best only transitional, and, in the words of one architect speaking about Pius XII’s new Holy Week, “a battering ram” with the sole purpose of breaking into and overthrowing our rightful inheritance.

In devoting his life’s scholarship, his eloquence of speech and pen, and his many musical gifts to the Church’s sacred rites, Kwasniewski continues to demonstrate his unreserved devotion of mind, heart, and strength to God. Perhaps in this time of preparation for the Nativity of Christ and anticipating the new year of grace, we may ponder how to do the same. We may not be scholars, but we can at least read; we may not be musicians, but we can open the ears of our hearts; and we may not yet be Saints, but we can and must throw ourselves headlong into the liturgical life the way children throw themselves into the arms of their mothers. The liturgy is our mother in that it brings Christ to us. Do we not owe our mother the deepest love? Ought we not labor and fight to defend her? For Kwasniewski, the answer is clear:

In the end, Catholics will be traditional, or they will not be at all. This realization brings both comfort in the midst of trial and a sense of growing responsibility: tradition is not something that automatically prevails in us, without our effort, as neither does orthodoxy or good morals. Just as we have to school ourselves in Catholic doctrine and labor against our fallen human nature with asceticism and conscious aspiration to virtue, so too we need to learn (or re-learn) our traditions in all their amplitude and richness, or they will evaporate under the scorching winds of late modernity. A contemporary writer, Lewis Hyde, coined the phrase “the labor of gratitude”: truly taking possession of a heritage means being aware of its value, being grateful to God for it, laboring to get to know it better, and working to ensure that it remains alive and well—that it will, in spite of every obstacle, be passed on to the future (29-30).

The Once and Future Roman Rite, a hardcover book from TAN, contains twelve substantial chapters which expound on the aforementioned topics as well as others such as the Roman Canon and the papacy. It contains several delightful illustrations, and Martin Mosebach provides a beautiful Foreword. Kwasniewski concludes his book with an epilogue of stirring “Oppositions,” a lengthy appendix consisting of highly revelatory passages on liturgical reform from Paul VI, and a detailed index. I can unreservedly recommend this book for all who are interested in serious discussions of the Roman rite—its glorious past and its guaranteed future.

Credit: Source link