Thirty-seven years after his assassination, a host of authors joined an initiative to commemorate Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali’s “art of resistance” with a poster.

The tribute depicts each artist’s own hero from behind, the same way Ali always drew his protagonist. Together with him they call for an end to the horror of war.

In Arabic, and also in Hebrew, a name is not only the identification of a person, but also marks their life, their mission, their destiny.

Naji al-Ali means “survivor,” a name that could not have been more apt for the cartoonist. Born in 1938, in Al-Shajara, a village in Galilee between Tiberias and Nazareth, he has “survived” escapes, exiles, threats, wars. In the 1950s, as the oil industry boomed in the Gulf countries, young people were attracted by the work available. In 1957, Ali migrated to the Gulf.

Two years later, back in Lebanon, he enrolled in the Beirut Academy of Fine Arts for a brief period, and became involved in politics. He had problems with Lebanese justice, and was imprisoned in 1961.

On leaving prison, he traveled to Tyre, where he taught at a drawing school and was fortunate enough to meet Ghassan Kanafani, the editor of Al Hurriyya (“Freedom”) magazine.

Kanafani was the first to publish his cartoons, launching him into the world of professional cartoonists. In 1963 he found work in Kuwait, collaborating with a weekly newspaper and the daily As-Siyasat (“The Policies”).

But there he suffered great disappointment as his friends turned away from him to live a life of luxury. In Lebanon he had many friends with whom he protested and struggled. Together with them he also went to prison. Then they became new people, insensitive, distracted, and forgot their duty to their compatriots and others locked up in refugee camps.

Handala

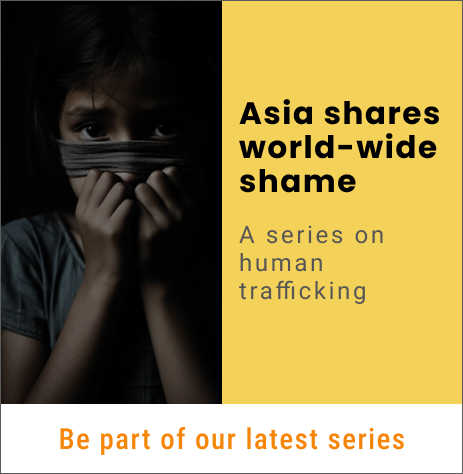

In Kuwait, Handala, the principal character in his cartoons, was born in the pages of the newspaper where Naji worked. He is a poor, Palestinian child from the Ain al-Hilweh Refugee Camp. He is about 10 years old, and will always be 10 years old; his hair is sparse, shaggy like that of a hedgehog; he walks barefoot; he is dressed in rags, like a peasant, with a conspicuous patch sewn on the shoulders.

One characteristic distinguishes him from other cartoon heroes: he is never drawn from the front, but always from the back.

His face is unfamiliar; he looks like a child without a smile; only his hands entwined behind his back can be seen. In reaction to the world that has turned its back on him, he does not show his face. Only when his land is free and he can return to it, will he be able to smile again and show us a joyful face.

Read the complete article here.

This article is brought to you by UCA News in association with “La Civiltà Cattolica.”

Credit: Source link