Women’s History Month traces its beginnings to the first International Women’s Day in 1911. In 1978, schools in Sonoma, California celebrated Women’s History Week with events designed around March 8 (International Women’s Day). Following a conference about women’s history in 1979, President Jimmy Carter issued a presidential proclamation declaring the week of March 8 as National Women’s History Week. In 1987, Congress designated the month of March as Women’s History Month.

Within Asheville Parks & Recreation’s system of parks, community centers, greenways, and other facilities, some are named after women who helped shape our city’s progress and left significant achievements along the way. In honor of Women’s History Month, we’ll highlight these public spaces throughout March.

Grace’s Garden

Building on the momentum of downtown revitalization that started in the late-1980s, the Asheville Urban Trail launched in 1991. Grace Pless was the guiding spirit of the focused volunteer committee that worked with the City of Asheville to install public art and narration to tell the fascinating history of our community along a circular 1.7-mile route in the city’s center.

Although Grace’s Garden isn’t technically part of the beloved civic amenity, the small shaded park with benches is just a few steps away from Stepping Out, the trail station that pays homage to the theaters and Grand Opera House that once flourished along Patton Avenue.

One block away, another station honors Asheville resident Elizabeth Blackwell, M.D., the first woman in the country to receive a medical degree and founder of the world’s first four-year medical college for women.

Stephens-Lee Community Center

Known as the Castle on the Hill, Stephens-Lee High School opened in 1923 on the former site of Catholic Hill School and was for many decades western North Carolina’s only secondary school for Black students, drawing pupils from Buncombe, Henderson, Madison, Yancey, and Transylvania counties.

The Lee in the name memorializes Hester Ford Lee, an educator at Catholic Hill School who died suddenly in 1922. She originally came to Asheville to teach in the city’s new public school system, becoming one of five teachers who opened Beaumont Street School in January 1888. After briefly moving to Tennessee, she returned with her husband Walter S. Lee in 1905. She again taught in Asheville City Schools from 1906 to 1916 and was principal of the “Southside Building” in 1912 and 1913 at a time when very few women of any race were given principalships.

An all-white school board closed Stephens-Lee as part of its desegregation plan in 1965 and most of the campus was bulldozed. The gymnasium remains as Stephens-Lee Community Center.

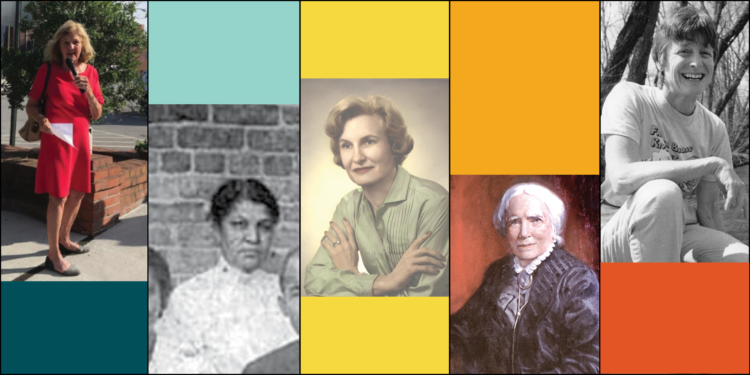

Wilma Dykeman Greenway

Born in Asheville, Wilma Dykeman lived all her life near the French Broad Broad River. A writer, speaker, teacher, historian, environmentalist, and strong supporter of linking economic development with environmental protection, she published 15 non-fiction books beginning with The French Broad in 1955 – making the first full-fledged economic argument against water pollution. She also wrote three novels, including The Tall Woman, the tale of a mountain woman who works to bring her community together after the Civil War, which sold more than 200,000 copies. For Neither Black Nor White, she and her husband James Stokely won The Hillman Prize for social justice in 1957.

She also worked as a newspaper columnist for almost five decades and her work appeared in many national publications. Both the City of Asheville and Buncombe County have adopted the Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Master Plan, a 17-mile greenway and park system intended to promote sustainable economic growth along the French Broad and Swannanoa Rivers. A greenway in the River Arts District that runs from Hill Street to Amboy Road is named in her honor.

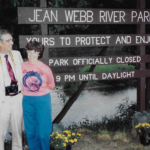

Jean Webb Park

Along the Wilma Dykeman Greenway, a little park with river access and benches is tucked under the Haywood Road bridge bearing the name of an Asheville native, Jean Williamson Webb. As the Executive Director of Quality Forward (predecessor to Asheville GreenWorks) from 1978 to 1983, she led trash cleanups around the community. With a love for the French Broad and a vision that it could be the center for a clean, vibrant Asheville, Webb organized the community’s first river cleanup day guided by the belief that if people used and enjoyed the river, then they would take care of it.

Along the Wilma Dykeman Greenway, a little park with river access and benches is tucked under the Haywood Road bridge bearing the name of an Asheville native, Jean Williamson Webb. As the Executive Director of Quality Forward (predecessor to Asheville GreenWorks) from 1978 to 1983, she led trash cleanups around the community. With a love for the French Broad and a vision that it could be the center for a clean, vibrant Asheville, Webb organized the community’s first river cleanup day guided by the belief that if people used and enjoyed the river, then they would take care of it.

As president of the French Broad River Foundation, Webb later helped organize Riverfest to support the foundation, worked with City and County leaders to develop access to the river, and organized Streamwatch groups to monitor pollution. Slowly, all these efforts began to make a difference and led to the formation of Riverlink. She also served as president of that organization, working closely with founding director, friend, and fellow visionary Karen Cragnolin (whose enormous contributions will be memorialized by a park bearing her name along the French Broad River Greenway).

She once said, “I am committed to this community. I just hope that people will realize the value of the beauty around us.” Her work, hope, and commitment transformed not only the river, but Asheville.

(Special thanks to Laura Webb and Julia Webb Gaskin for photos and biographical information.)

Check back next week for the histories behind Tempie Avery Montford Community Center, Augusta Barnet Park, Leah Chiles Park, Ann Patton Joyce Park, and Hazel Robinson Amphitheater. Previously, we’ve highlighted community centers and parks named after prominent Black individuals.

Credit: Source link