SPOILERS AHEAD

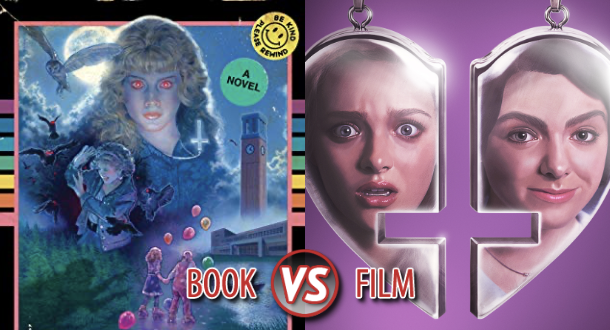

The 2022 film My Best Friend’s Exorcism, adapted from the 2016 novel of the same name by Grady Hendrix, enters the much-bloated cinematic lexicon of demonic possession movies, but with much more humor and far less religious oppressiveness. (The subgenre’s progenitor The Exorcist is, first and foremost, a Catholic propaganda film that spawned countless imitators, all rife with the same black and white, good versus evil morality).

Written for the screen by Jenna Lamia and directed by Damon Thomas, the narrative centers around Abby Rivers (Elsie Fisher) and her titular best friend Gretchen (Amiah Miller), who, after a misguided exploration of a supposedly haunted building out in the woods, falls into the clutches of a wicked entity hell-bent on destroying the lives of everyone around her. Abbie suffers intense psychological torment at the hands of the thing that used to be Gretchen, while Margaret (Rachel Ogechi Kanu), their athletic “big girl” friend who dreams of being skinny, gets tricked into drinking supernaturally-charged tapeworms, and their other friend Glee (Cathy Ang) receives love letters from a supposed secret admirer (actually Gretchen), which threatens to expose the “forbidden love” she harbors for another. After numerous failed attempts to cure Gretchen of her demonic ailment, Abby seeks the help of Christian Lemon (Christopher Lowell), the littlest brother of a touring, Jesus-worshipping muscle man show who claims to have the power of discernment and the ability to exorcise the entity — revealed to be Andras, one of the Great Marquises of Hell — from her friend’s body. Naturally, things don’t quite go as planned, and get much, much worse before they get better.

[It’s] an overall entertaining picture that at times seems afraid to really “go there” when it needs to.

The movie’s plot rather faithfully follows that of the novel, with only a few diversions. However, the changes made, while on the surface minor, create a significant divide between book and film, with the former being a deceptively nuanced exploration of the power of friendship, and the latter an overall entertaining picture that at times seems afraid to really “go there” when it needs to.

To begin with, both versions of this narrative take place in the 1980s, a decade recognized as both excessive and repressive at the same time. On top of this, much of the action unfolds at an expensive private school in the American South. In Hendrix’s novel, the institutional racism and inherent biases of this backdrop often come to the fore in the form of complete oblivion from the characters when confronted with them — for instance, the highly problematic “Slave Day” at the academy, in which students “purchase” other students and force them into acts of servitude and humiliation in the name of charity and school spirit. The author writes, “…in 1988 no one dreamed that [Slave Day] could possibly be offensive. It was tradition.”

Fittingly, all the major characters in the book are white, accurately representing the privileged, casually racist environment in which they live. The film, however, includes a more diverse cast, with Margaret now Black and Glee now Asian (and secretly queer). The movie also tones down the clear yet unspoken segregation present at the school, making it more likely the academy would have a few non-white students enrolled there. Moreover, while the primary characters in Hendrix’s novel are nominally popular and all wealthy (except for Abbie, who attends on a scholarship), they skew a bit more misfit than their peers, so it would make sense that the girls who don’t look like everyone else, at least in terms of their skin tone, would gravitate toward Abbie, who is poor and saddled with bad acne, and Gretchen, whose parents are overtly religious and who, for all intents and purposes, is kind of a weirdo.

But while diversifying the characters is welcome in this context, it feels as if the filmmakers aren’t altogether prepared to fully handle the changes they’ve made. Margaret’s character arc works to critique thinness as the de facto beauty standard for women, and the casting of a Black actress opens the door to further examine the projection of this white-influenced beauty standard onto Black women’s bodies. However, while the door is open, Lamia and Thomas don’t really walk through it. This isn’t to say the narrative necessarily suffers as a result of these lack of steps — neither the book nor this adaptation are primarily concerned with social issues, after all — but it does seem like the matter could have been handled in a more substantiative way than it is.

More egregious, though, is the depiction of Glee’s queerness. In the book, the character is secretly attracted to the school’s male chaplain, with Gretchen writing fake love letters from the man in order to turn Glee’s crush into a full-on obsession. This cruel trick results in Glee attempting to commit suicide after he rejects her advances, prompting Glee’s family to whisk her out of town and forever damning her as that “crazy girl” who stalked a priest and tried to jump off the school’s clock tower. In the film, Glee actually has a secret crush on Margaret, giving Gretchen’s machinations added weight — to be outed, especially in a socially conservative environment, was absolutely devastating in the 1980s. And while Margaret does discover Glee’s feelings and subsequently rejects her, Gretchen’s ultimate goal isn’t to publicly humiliate and exile the girl; instead, the love note game was merely a ploy to get Glee alone so she could feed her a peanut laced brownie, which, given she is highly allergic, nearly kills her. The demon Andras loves to sow discord and disharmony by preying on people’s insecurities and hidden fears, so it makes no sense that its ultimate prank is to exploit Glee’s peanut allergy, rather than tear her apart over a “dirty little secret.” One wonders why the filmmakers even bothered with the queer subplot if they weren’t willing to take it to its logical conclusion.

Though their roles are lacking certain dramatic possibilities, both Ogechi Kanu and Ang are terrific. Lowell as Brother Lemon brings some goofy energy to the proceedings, though his average body does rob viewers the chance to see a super-jacked but morally tormented exorcist hurl insults and table salt at a demonically-possessed teenager. Miller and the always engaging Fisher make a great pair, though, as with other performers in the film, they don’t get the chance to really flex their acting abilities, especially in the third act during the penultimate exorcism, when Abbie’s deep love for her friend proves more powerful than any dusty religious texts in saving Gretchen’s life. Technically the moment occurs, but it’s rushed in favor of a literal battle with a CGI demon that forms, T-1000 style, from a pile of Gretchen’s puke. The sweeping dramatic heft seen in Hendrix’s novel is absent here.

All this isn’t to say My Best Friend’s Exorcism is a bad movie. It features solid performances from the cast, a lot of wit, good special effects, and a rockin’ new wave soundtrack. In other words, it’s Stranger Things but with a girl-centric cast and a much darker sense of humor. It’s entertaining overall, and a fun way to ingest a possession narrative without all the dogmatic trimmings. It’s just that its literary predecessor delivers on all these fronts while also telling a genuinely moving and bittersweet coming-of-age tale, one that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. The film is good, but the novel, at the end of the day, is pretty great.

Get My Best Friend’s Exorcism at Bookshop or Amazon

Credit: Source link