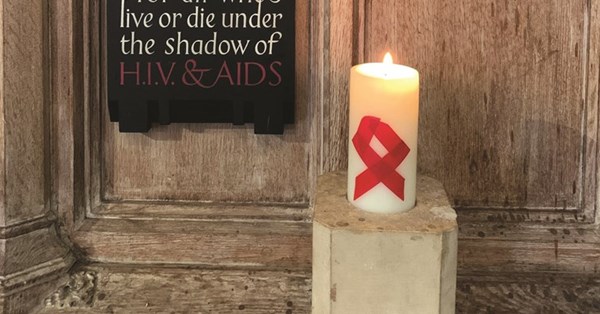

THIRTY-ONE years ago, a decision was made by the then Provost of Southwark, the theologian and historian David Edwards, and the Chapter at the time to designate St Andrew’s Chapel, in the retrochoir of Southwark Cathedral, as the AIDS chapel.

At that stage, there was a real crisis around HIV/AIDS, and the Church was at the heart of it. As the recent Channel 4 series It’s a Sin so graphically and painfully showed, the implications of contracting HIV were massive for the individuals and their network and families [Comment, 29 January 2021; Television, 5 February 2021].

It wasn’t just that people were dying, but that they were being stigmatised and hated. Some Christians described it as God’s vengeance, God’s revenge on a sinful group of people. If that is what God is like, well, to be honest I’m not interested in believing in him. As the Pet Shop Boys sang, “It’s a sin”; and it described people’s attitude then and continues to describe some people’s attitude now. It’s a sin — not so much contracting HIV, but being gay, being part of the LGBTQI+ community.

So, Southwark Cathedral, whose three words to describe ourselves and our values are “inclusive, faithful, radical”, decided to stand not with that condemning voice of the Church, but with the affirming. The chapel was dedicated, and a commitment was made: every Saturday, the mass, the eucharist, would be offered for those “living with or affected by HIV/AIDS”. As was reported recently in the Church Times [Features, 26 November 2021], we have stayed faithful to that commitment: we always pray, each Saturday, and have done, year in, year out, the most consistent witness and act of solidarity within the Church of England for this particular group of people.

We do this with Grace Cathedral, in San Francisco, the only other Anglican cathedral in the world to have such a chapel. Why San Francisco and Southwark? Because we are both in touch with the LGBTQI+ community, and have been and will be, because it is our community and our congregation.

IT IS ironic — and that word hardly does it justice — that, just as I was thinking about what I would say to you this morning as you begin your conference, that a member of the General Synod has put down a private member’s motion [PMM] [News, 10 June].

Sam Margrave is a member of the House of Laity, and, as he is entitled to do, has put down a motion, which will need 100 signatures to then be debated on the floor of Synod. He has asked the Synod that, while “affirming that God loves all people irrespective of their sexual orientation, nevertheless consider that the ‘Pride’ rainbow flag and what it represents in terms of the ordering of lives and relationships is contrary to the word of God”.

In the motion, the proposer calls for the House of Bishops to “state that support for Pride (including use of the rainbow flag and participation in Pride events) is incompatible with the Christian faith”. He argues that the LGBTQI+ “agenda” is “contrary to scriptural teaching and doctrine by promoting sexuality and promiscuity, and by the denial of the distinction between male and female”.

Sam also asked the Archbishop’s Council to pass legislation that would “prohibit the display of any political or other campaigning flags in or on church buildings”. He said that he was spurred on to put forward his motion because of the “significant” number of churches celebrating Pride Month. He said: “The number of churches, cathedrals, and clergy endorsing Pride, which promotes values contrary to scripture, has been significant this year. Whether or not they agree with the proposal, we as a church need to discuss the Church’s approach to Pride and the increasing use of political flags inside our churches.”

THIS is the reality into which the Living in Love and Faith [LLF] process has been holding its conversations and consultation. For me, this PMM gives the game away — that, as much as would like it not to be so, there is a homophobic element within the structures of the Church of England that isn’t interested in moving forwards.

LLF began in November 2020 when all the study material was published. The four key principles behind the process are:

- Learning together about the subject matter, about each other, about God, and about our calling as a Church.

- Listening to what is emerging from our learning together about identity, sexuality, relationships and marriage, and about our life together as church communities and as a national Church.

- Discerning what the Holy Spirit is saying to the Church today.

- Deciding how discernment is translated into a way forward for the Church.

I asked the person who led on this in the diocese for some comments. This is what they said to me.

“From talking to the other advocates around the country, I think that it has been a more profoundly challenging thing to do in some other parts of the country, where far fewer people are open and want to talk about how they live their lives.

“I also think that there is a real sense of wondering how much this will change anything, and whether there is any real sense of moving towards a resolution. I think, too, that there is also a sense that the process returning to the bishops is not necessarily what people would want.

“Overall, here in Southwark, it has seemed to be a worthwhile thing to do, although [some] have found some of what has gone on very challenging and [have] wanted to protest what has happened. But many have engaged in a constructive and helpful way, and it might be that beginning conversations about how we live is a helpful way forward.”

NOW, I need to be honest and say that I haven’t taken part in this LLF process beyond what we have done in the General Synod. Why? Well, I suspect that I, like many people and especially those of us who have been talking about this issue for as long as we have known that there was an issue, have just had enough of it. It’s not so much long grass that we seem to be in, but more like a swamp which is impossible to escape and is sucking the life out of us.

Yet I recognise that, for many people and for some congregations, the conversation has needed to take place and the issues to be explored in a facilitated way. The course has provided some forms of facilitation — and I recognise that.

The principles are, however, important. We have to be able to learn together — and that requires us to be open-minded, while also being willing to engage intelligently with scripture. We have to listen, and that does mean listening to people with whom we disagree intensely. I will say more about that in a moment.

We have to be prepared to do that process of discernment, but who is going to do that — General Synod, the House of Bishops, clergy, parishes? Who really is listening for the gentle beating of the wings of the Holy Spirit? Given the processes around the ordination of women, I am not sure I entirely trust the ability of the Church of England to hear “what the Spirit is saying to the churches”, as St John in the book of Revelation would describe it.

Then we have to decide, and that is going to be the really tricky point in the whole process. Do we ultimately decide that we can’t decide, and so decide to disagree into the future? In many ways, that is exactly how we have made decisions so far — around the remarriage of those previously married, around the ordination of women. We have used local decision-making, conscience, and fig leaves like “mutual flourishing” to move forward.

If that is the outcome, then what has stopped us so far? Why have we not simply decided not to decide and instead decided to disagree and move on with some process of the accommodation of differing views?

I am told that homosexuality is an issue not like divorce — though Jesus spoke so openly and in such harsh terms about it. Nor is it like the ministry of ordained women — though St Paul, the poster boy for so many of the proof texts, is equally hard on the role of women in the formal life of the Church. Is it different because it is about sex — not gender — about sexual activity, and people in the Church simply cannot stomach admitting that people have sex and might even enjoy it?

And if it is not just about homophobia, but some kind of geno- or eroto-phobia, then how are we ever going to grow up?

Living in Love and Faith, in its very title, seems to suggest the way forward, though we might still flounder on the rocks. Unless there are more delaying tactics hidden under the mitres of fearful bishops, we have to move forward: the days of long grass have to be over and almost behind us. We have to now do what it has said on the can: we have to live in love and faith.

I SAID that I would come back to listening, which is the second of those four principles. The best part of the journey we have been on so far, for me, has been the shared conversations. You may remember them — you may even have been part of them. I was “lucky” enough to be involved in three shared conversations. The first was in the initial regional residential phase; the second was as part of the General Synod, one year in York; the third was another residential one in the diocese.

The low point in those, for me, was in the wash-up session of the final one of those three. Our bishop had come along to hear how we had got on. We went round the room, just making general reflections — “nice”, “positive”, “interesting”, the kind of thing Christians say when there is a bishop in the room.

But there was a young curate sat near me — I was by then the Dean — who, in front of everyone, turned to me and said: “Andrew, you need to know that you cannot be saved.” I thanked him for his courage in saying that to me, saying what in all sincerity he believed to be true. Inside, I was wondering how he had the arrogance and the audacity to say that to his dean in front of his bishop — but I know that I am an old git of a different generation!

I responded that I had always relied upon the mercy of God and would continue to do so. But it stays with me. Maybe I cannot be saved.

More positively, at the first set of conversations, I met a conservative Evangelical from the diocese, whom I knew by sight, but no more than that. In the bar sessions in the evening — which are often the most productive times — we started talking. And we agreed to keep the conversation going.

So, for the past six years, we have met every couple of months, and shared a meal and talked — about sex, yes, but much more about mission and the parish, and church and people and sex. But we discovered that what we had in common was so much more, and so much more important, than what we thought — imagined — divided us. We are now good friends.

St Luke’s is the most inclusive of the Gospels — but then, he was a doctor, and so had encountered people at their most vulnerable and most real. In his Passion account, he mentions this, which no one else picks up on: “That same day Herod and Pilate became friends with each other; before this they had been enemies” (Luke 23.12).

Who had reconciled them? Jesus. It is only through Jesus, who embraces us and loves us and died for us, who lived in love that we might live in faith, that we can possibly find our way forward — and that, my friends, I have to believe.

The Very Revd Andrew Nunn is the Dean of Southwark.

This is the text of an address delivered at the second national conference of MOSAIC (Movement of Supporting Anglicans for An Inclusive Church), on Saturday.

mosaic-anglicans.org

Credit: Source link