When Haitian slaves successfully revolted against French colonial rule in the early 19th century, White lawmakers in South Carolina tightened restrictions around the importation of Haitian slaves into the state, fearful of a similar uprising.

In those days, slavery was seen by Whites as a necessary tool for the economic stability of the South and the atrocity was supported even by religious institutions, like the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston, whose early church leaders backed the inhumane practice.

Now, 200 years after the diocese was founded in 1820, the church has its first Black bishop — Jacques Fabre, a native of Haiti. The symbolic power of the appointment cannot be overstated.

“I see this as really a poke in the eye of sorts,” said Arthur McFarland, former Supreme Knight and CEO of the Knights of Peter Claver Inc., the nation’s largest Black Catholic organization.

The selection “speaks volumes in terms of where we have come and why this is so significant to us as African Americans,” he added, saying he and other Black Catholics in the state hope Fabre appreciates and recognizes the monumental feat.

But while the symbolism is much to celebrate, African Americans throughout the diocese are also hoping Fabre’s installment marks a turning point for the diocese in that the new bishop will openly acknowledge the religious body’s complex history. That includes being attentive to the concerns of Catholics who have long felt ignored by the religious institution by embracing the diocese’s growing diversity with more evangelism efforts and helping to inform White Catholics about issues pertaining to social justice.

Fabre was born Nov. 13, 1955, in Port-Au-Prince. One of six children, he grew up in a Catholic family. He also loved sports, becoming an avid soccer player who continued the sport when he immigrated to New York at age 16 in both high school and college. He quit only after injuring his ankle.

Bishop Jacques Fabre-Jeune

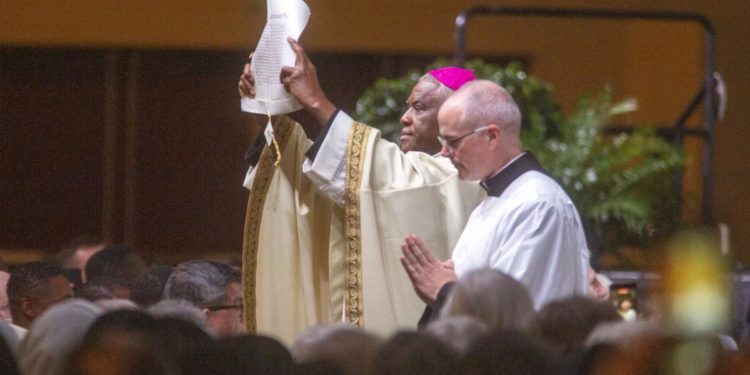

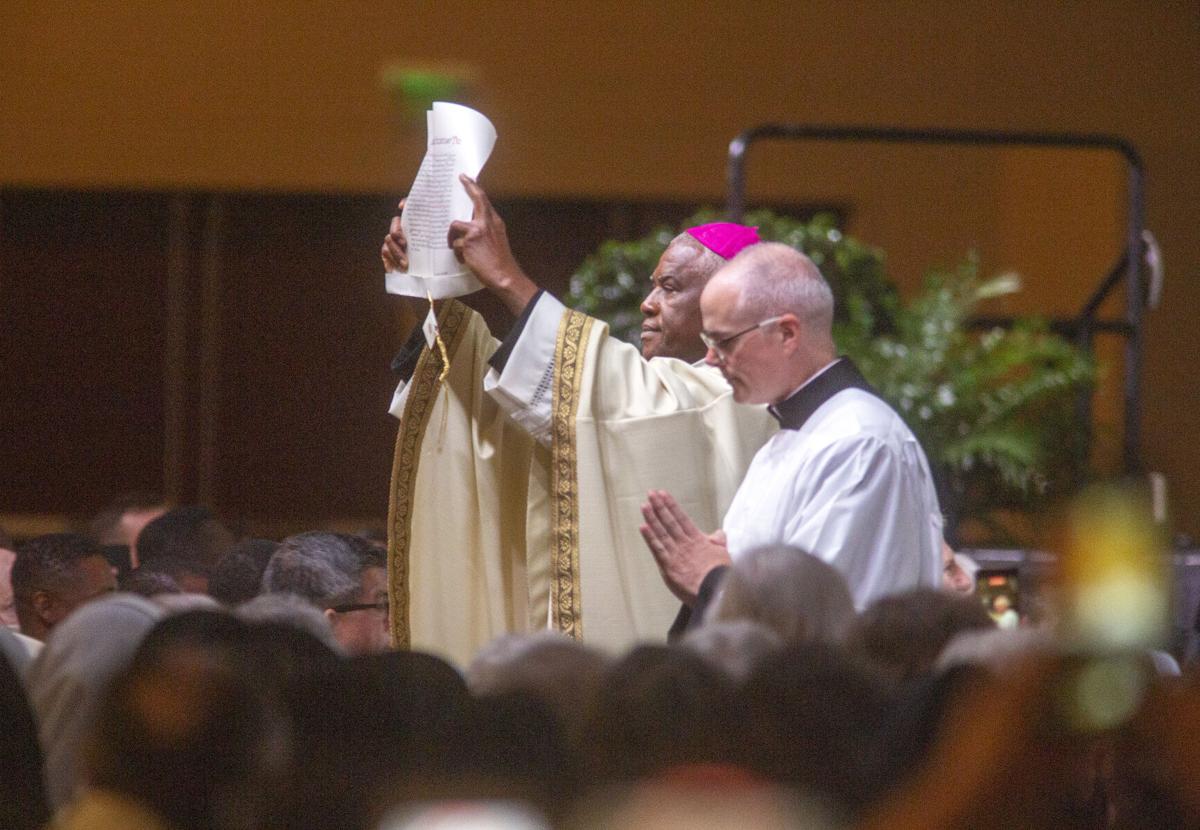

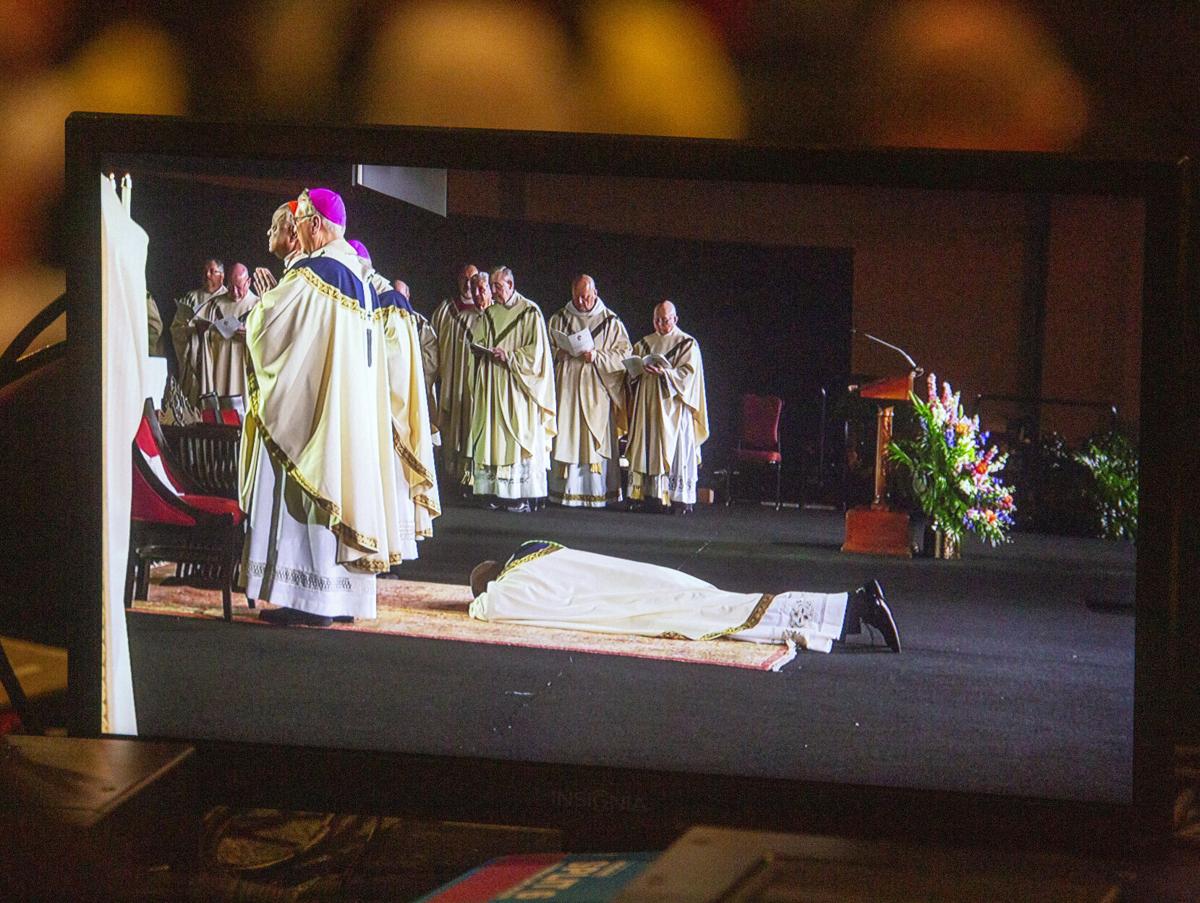

Parishioners bring offerings to Bishop Jacques Fabre during his Episcopal Ordination and Installation naming him the 14th Bishop of the Charleston Catholic Diocese at the Charleston Area Convention Center May 13, 2022. Fabre is replacing Bishop Robert Guglielmone. Brad Nettles/Staff

Haiti’s political backdrop and high poverty shaped Fabre’s theology into one that embraces the ideas of freedom and serving the needy. After beginning his journey into the priesthood in the 1980s, Fabre would embark on a ministry that prioritized mission work, serving as chaplain to Haitian refugees in Cuba, and administrator for several missions with the Catholic Church in America.

Fabre now leads a diocese in one of the nation’s poorest states with a poverty rate of around 14 percent. Fabre’s attempt to serve those in need begins first with questioning how it is that a state in a first-world country has so many who struggle to meet basic needs.

“We can continue to say things are bad and we can find justifications for it historically,” he said. “But are we going to keep saying the same thing when we have the possibility to change it?”

Increasing diversity

There are about 200,000 Catholics in the South Carolina diocese. The bishop wants to see an increase in the number of Black Catholics. African Americans make up less than 2 percent of the diocese’s membership. The religious group’s Hispanic population is growing and accounts for 20 percent. White members make up 70 percent.

Fabre said the low number of African American Catholics has to do with the fact that Blacks during slavery were not allowed to serve as priests because they lacked education due to racist laws prohibiting slaves from learning to read and write. Instead, Blacks formed congregations that eventually became part of Protestant denominations.

Attracting and growing the number of Black Catholics in South Carolina can be accomplished through more evangelism, he said.

“We have to present the good news from a Catholic perspective to anyone who is willing to accept it,” Fabre said. “Black Catholics will be part of that.”

He also is aware of the diocese’s growing Hispanic presence. Fabre said Latino Catholics bring a unique sense of joy into the faith that is expressed through their worship. One way the diocese can be attentive to that sector is through appointing Spanish-speaking priests.

Blacks are hoping they can see more Black priests who can relate to Black culture. The power to appoint priests lies solely in the bishop’s hands, so it’s an act that Fabre can address immediately, McFarland said. Such a move would go a long way for South Carolina’s Black population, which has been “really crying out for attention,” he said.

Blacks also will look to see whether Fabre talks to White Catholics about the racism that still exists within the church, McFarland said.

Other issues include the need for more women deacons.

“In the Black church — with Catholics as well as Protestants — the women are the workers in the church,” McFarland said. “I know that there are Black women who are ready to step up to the plate.”

African American Catholics will be anxious to see how Fabre steps into his role with more progressive thought. “His views on a number of issues that take it out of the conservative realm will be very important,” McFarland said.

Reexamining history

Fabre’s arrival also presents an opportunity to reexamine South Carolina’s Catholic roots.

Discussion around the history of Catholicism in the Palmetto State often begins with the diocese’s English priests in the 1700s, or the group’s first bishop — John England — in 1820, said Matthew Cressler, a College of Charleston religious studies professor and author of “Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration.”

But, as Cressler notes, Congolese Catholics had a presence in the state in the early 1700s. In 1491, there were Blacks in the Congo and West Africa who had converted to Catholicism before the area became a target for the slave trade. Some of these Congolese Catholics fought against oppression, playing a role in launching the Lowcountry’s 1739 Stono Rebellion, Cressler said.

“There’s a way in which Catholic history in South Carolina begins with Black Catholics — specifically African Catholics — who were Catholic before they came to the Americas,” Cressler said. “They weren’t converted as enslaved people. They brought their Catholicism with them.”

Fabre’s appointment is especially significant not only because of South Carolina’s racist past but also because of the role the diocese played during the era of slavery. Some of the church’s earliest bishops were prominent defenders of slavery, Cressler said.

It’s important for Fabre to acknowledge that troubled history, as well as the ways in which Blacks have helped shaped Catholicism in the Lowcountry, the professor said.

“I would love to see him in some way kind of acknowledge the deep roots of Black Catholicism in the making of the Lowcountry, the significance of black Catholicism worldwide and, and to be more attentive to the ways in which African-descended peoples have made the Lowcountry, certainly more than any of his predecessors would,” Cressler said.

Credit: Source link