BRONZEVILLE — Black Chicagoans have been revolutionaries and world changers, their impact spanning generations, from Harold Washington to Ida B. Wells, and Jean Baptiste Point du Sable to Chairman Fred Hampton.

While most people know the city’s first Black mayor and first non-Indigenous settler, there are plenty more Black Chicagoans whose work, art, activism and politics are part of how residents live and learn.

As Black History Month winds down, Block Club is celebrating the Black icons of the past. While some are well-known, others may not be. Consider this a list of some of the people worth knowing if you don’t already.

And make sure to join Block Club 7 p.m. Thursday for a virtual conversation with historian Shermann “Dilla” Thomas, activist Chairman Fred Hampton Jr. and “Folded Map” creator Tonika Lewis Johnson. They will talk about the ways Black history is Chicago history.

This free event will stream live on our YouTube channel and will be moderated by Block Club’s Pascal Sabino, who covers the West Side. You can RSVP here.

Lil Hardin Armstrong

“Lil” Armstrong is the woman who gave Louis his swag.

Born in Memphis in 1898 and moving to Chicago in 1918, Lillian “Lil” Hardin Armstrong was a classically trained pianist, composer, arranger and bandleader long before she met the iconic trumpeter in the early 1920s while they played in King Oliver’s band, according to the Memphis Music Hall of Fame. The band drew standing-room only crowds playing every night on the South Side, according to the Riverwalk Jazz radio series.

After the couple married in 1924, Hardin Armstrong was instrumental in launching her husband’s solo career and pushed him to leave King Oliver’s band, according to Riverwalk Jazz. She made over Armstrong so he’d look less country, according to the Memphis Music Hall of Fame. Her efforts worked and turned her husband into a sought-after star by the mid-1920s.

The couple split in the early 1930s, but Hardin Armstrong continued as a solo act and pianist, billing herself as “Ms. Louis Armstrong.” She stood out at a time when Black women were rarely headliners, relegated to members of a chorus line. She became a professional tailor in the mid-40s, according to the Memphis Music Hall of Fame, but she returned to performing for the next two decades.

Hardin Armstrong outlived her former husband by one month. She died in 1971 after collapsing during a performance in a televised memorial in Armstrong’s honor. She was 73.

A Bronzeville park was named after her in 2004.

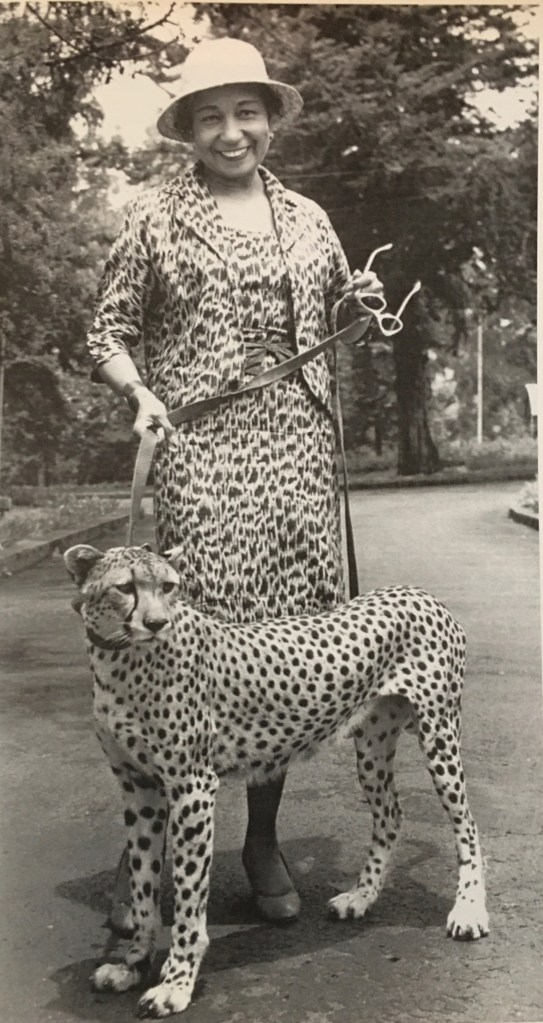

Etta Moten Barnett

A triple threat before the phrase was invented, singer, actor and philanthropist Etta Moten Barnett was one of the most sought-after entertainers of her time.

Credit: Provided/Lynne McDaniel

Credit: Provided/Lynne McDanielBorn in Texas in 1901, Moten Barnett married and had three children. The couple divorced and Moten Barnett enrolled at University of Kansas to study voice and drama, performing with a popular local gospel group to pay her way through school, according to the Chicago Public Library.

After graduating, Moten Barnett headed to Broadway, performing in “Lysistrata” and “Sugar Hill.” She switched her focus to film, dubbing vocals before making her on-screen debut in 1933. Her performance in “The Gold Diggers of 1933” captured the attention of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who invited Moten Barnett to sing at President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s birthday. She was the first Black woman to perform at the White House.

Moten Barnett headed to Chicago after marrying Claude Barnett, founder and director of the Associated Negro Press, in 1934.

Moten Barnett took on her signature role of Bess in George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” in 1942. She originally turned down the role because it didn’t match her vocal range, but she changed her mind and the opera became a smash hit, according to the Chicago Public Library.

After Claude Barnett husband died in 1967, Moten Barnett turned her attention to philanthropy, supporting causes and organizations like the DuSable Museum, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Field Museum, the South Side Community Art Center and the NAACP, according to the library.

The philanthropist was as much known for her quick wit as she was for her beauty, the latter of which led Sidney Poitier to write a gushing testimony for her 100th birthday.

Moten Barnett died in 2004 at 102. Moten Barnett’s daughter donated 27 boxes of photos, manuscripts, press clippings, letters and other archives from her mother’s life to the Chicago Public Library in 2007.

The Bronzeville home at 3619 S. King Drive where Moten Barnett and her husband once lived still stands and hosted an estate sale of her prized possessions last year.

Margaret Burroughs

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Wikimedia CommonsA teacher, poet, activist and artist, Margaret Burroughs perhaps is best known as the founder of the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art, now the DuSable Museum of African American History, 740 E. 56th Place.

Burroughs, originally from Louisiana, grew up in Englewood. She attended Englewood High School, Chicago Teachers College and the Art Institute of Chicago, according to literary organization The Poetry Foundation. She taught at DuSable High School for 20 years. The poet and scholar wrote and illustrated several children’s books and poetry collections while painting, sculpting and printmaking, all of her work deeply rooted in the Black experience.

Burroughs, husband Charles Burroughs and a small group of organizers started what became the DuSable Museum out of the first floor of the Burroughs’ 3806 S. Michigan Ave. home in 1961, according to the museum. It was across the street from the South Side Community Arts Center, which Burroughs helped establish when she was just 22, according to her The HistoryMakers profile.

At the time, Margaret Burroughs said it was “the only [museum] that grew out of the Indigenous Black community,” according to the DuSable. It was renamed in honor of Du Sable in 1968.

Mayor Harold Washington named Feb. 1, 1986, “Dr. Margaret Burroughs Day,” according to the HistoryMakers. She was inducted into the Chicago Women’s Hall of Fame in 1989 and the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame in 2015.

Burroughs died in 2010 at 95.

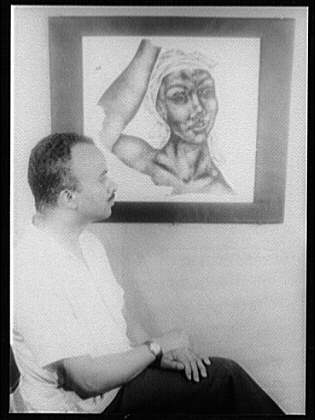

Eldzier Cortor

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Wikimedia CommonsA member of the Black Chicago Renaissance, Cortor — a schoolmate of Burroughs at Englewood High — was renowned for his captivating paintings of Black women in a career spanning seven decades.

Born in 1916 in Virginia, Cortor wanted to become a cartoon artist after seeing a Walt Disney film, his son, Michael Cortor, said at an Art Institute of Chicago event in 2020.

While at Englewood High, Cortor and other students took weekend art lessons at the Art Institute, Michael Cortor said. Cortor went on to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where trips to the Field Museum to study African artifacts inspired his art, his son said. He also helped launch the South Side Community Arts Center, his son said.

In the 1940s, Cortor received fellowships from the Julius Rosenwald Foundation to spend time off the Georgia/South Carolina coast, where he immersed himself in Gullah culture while painting the island’s inhabitants, his style elongating faces and body parts, according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. He’d travel throughout the Caribbean as a Guggenheim Fellow studying surrealism.

Cortor is considered the first Black artist to center nude Black women, and for that he had his fair share of critics accusing him of adding to their sexual exploitation. For him, it was about empowerment, saying, “The Black woman represents the Black race,” according to the Smithsonian.

Cortor died a month shy of his 100th birthday in 2015, after he’d continued painting through his late 90s, his son said. His work can be seen at the Art Institute.

Carl Cotton

This Washington Park native was the Field Museum’s first Black taxidermist, preparing specimens for the museum for 25 years. But for decades, even museum staff and leaders knew little about him or his work.

Born in 1918, Cotton showed an early interest in taxidermy, stuffing squirrels and other small animals, historian Timuel Black told the Field Museum in 2020. He joked that “cats and rats ran when they saw Carl.”

Despite Cotton’s talent, getting in the door was difficult. The 22-year-old wrote to the Field’s director in 1940 seeking a taxidermy job, but he didn’t have an advanced degree in the field and was turned down, according to Tori Lee, who developed the recent exhibition showcasing Cotton’s work. After serving in the Navy, Cotton wrote a longer letter in August 1947 offering to volunteer, Lee said. Museum leaders were so impressed with him that he was hired the following week and given a full-time job a month later, Lee said.

Cotton became the museum’s first staff member of the exhibitions department in 1966, allowing him to showcase his skill in taxidermy across many classes of animals, according to Chicago Magazine. It was through his work he would tell stories of how animals lived and died, his passion for nature evident in the exhibits he helped create.

Over the years, Cotton continued practicing his craft at home — his grandson told Chicago Magazine he remembers Cotton’s freezer always being full with animals ready to be preserved and stuffed. Cotton died in 1971.

In 2019, Lee set out to showcase Cotton’s life at work at the museum after employees looking for people to honor for Black History Month stumbled upon a photo of Cotton. Not knowing there’d ever been a Black taxidermist at the museum, Lee tracked down family members to create “A Natural Talent: The Taxidermy of Carl Cotton” exhibition, cataloging every specimen stuffed by his hand while sharing the story of his life.

Charles C. Dawson

A Georgia native who worked as a Pullman porter to pay his art school tuition, Charles Dawson was the go-to graphic designer for Black-owned cosmetology schools, often designing their ads. He also designed posters for legendary Black director Oscar Micheaux.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Wikimedia CommonsBorn in 1889, Dawson trained at the Tuskegee Institute and the Art Institute of Chicago, according to a WTTW profile. When he graduated from art school in 1917, he enlisted in the Army and was sent to France as a buffalo soldier, part of the only segregated combat unit that saw battle in World War I, according to WTTW. He began his design career when he returned to Chicago.

Dawson was also a painter and printmaker who was one of the faces of the New Negro Movement. Epitomized by the anthology, “The New Negro,” educator Alain Locke sought to reshape Black identity, question white standards and patriarchy and push self-expression and Black pride.

As part of that, Dawson was among several artists whose work was featured in a 1927 “The Negro in Art Week” exhibition at the Art Institute. The Chicago Woman’s Club organized the event, and Dawson designed the cover of the catalogue featuring an oversized Egyptian pharaoh.

Dawson also oversaw the creation of 33 5-foot-wide dioramas commemorating pivotal moments in Black history for the American Negro Exposition in 1940, according to CBS News. The dioramas portrayed moments like when explorer Matthew Henson reached the North Pole in 1909 and the building of the Sphinx. Artists including Jacob Lawrence and Charles White were among those who created the works.

Dawson spent 11 years as curator of Tuskegee University’s Museum of Negro Art and retired to New Hope, Pennsylvania, where he died in 1981. He was 91.

Oscar Stanton De Priest

Chicago’s first Black alderman was the son of a formerly enslaved couple who fled from Florence, Alabama, to Salina, Kansas, to escape post-Reconstruction violence erupting in the South.

Credit: Provided.

Credit: Provided.Born in 1871, De Priest moved to Dayton, Ohio, when he was 17 and landed in Chicago a year later, according to the White House Historical Association. Once there, the trained bookkeeper found work as a contractor and real estate broker, helping Black residents attain homeownership.

After a stint on the Cook County Board of Commissioners, De Priest was elected to the City Council, representing the 2nd Ward from 1915-17. A bribery charge cut short his time in City Council even though famed attorney Clarence Darrow secured an acquittal.

De Priest founded the People’s Movement Club, a Black political organization that saw its influence grew over the next several years, positioning De Priest as a top Black politician under Mayor William Hale Thompson.

After Republican Congressman Martin B. Madden died unexpectedly in 1928, Thompson backed De Priest for the seat. He fought several other Black challengers to win the seat in 1929, becoming the first Black man elected to Congress in the 20th century, according the House of Representatives. He served three terms in the House, battling racial discrimination, segregation and lynching, and fighting for the right for Black people to eat at the House restaurant instead of in in the basement.

De Priest’s bid for a fourth term failed when he lost to New Deal Democrat Arthur Mitchell. He returned to City Council as a 3rd Ward alderman 1943-47. He died in 1951 at age 80.

De Priest’s house at 4536 S. King Drive is a national landmark.

Hazel M. Johnson

The “Mother of Environmental Justice” spent most of her life fighting for clean air and water on the Southeast Side, organizing her Altgeld Gardens neighbors against the Chicago Housing Authority to fix the development’s contaminated drinking water.

Born in 1935, Johnson grew up in an area of New Orleans that has been called “cancer alley,” according to a WTTW profile. She was the only one of four siblings to live past their first birthday, according to WTTW. She moved to Chicago with her husband, John Johnson, in the mid-’50s.

John Johnson’s death from cancer in 1969, as well as the deaths of four young neighborhood children, spurred Hazel Johnson’s activism, according to WTTW.

Johnson learned from television the South Side had the highest cancer rate in Chicago, according to the Chicago Public Library. She began investigating environmental conditions in her area, tracing the bad smells, chronic respiratory illnesses and high cancer rates to the land on which Altgeld Gardens was built, and the dozens of landfills, leaking underground storage tanks, industrial facilities, factories and other hazards that created a “toxic doughnut” of the area, according to WTTW.

While Johnson meticulously detailed health information from neighbors, she galvanized residents to force CHA to address the hazards plaguing the housing project, from the asbestos-lined walls to the contaminated drinking water.

Johnson founded People for Community Recovery in 1979 to start protesting major polluters in the area, according to the public library. Throughout the 1980s, she galvanized communities of color outside Chicago around environmental justice, and she often was the only nonwhite organizer at major environmental conferences. It was at the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1992 where Johnson got her nickname, according to the library.

Johnson died in 2011 at 75. She lived in Altgeld Gardens until the end of her life, and her daughter, Cheryl Johnson, took over the People for Community Recovery work.

Rep. Bobby Rush has led efforts to honor the late environmentalist with a commemorative postage stamp, introducing a bill that would declare April “Hazel M. Johnson Environmental Justice Month.” The bill is working its way through Congress.

Father John Augustus Tolton

“Father Gus” was the country’s first publicly known Black priest — and the first to make Chicago his home.

Born into slavery in Missouri in 1854, Tolton was raised Catholic; his mother was baptized as Catholic because the people who enslaved her were of the faith, according to the Archdiocese of Chicago.

Credit: Wikipedia Commons.

Credit: Wikipedia Commons.Tolton’s family escaped from slavery in 1862 by crossing the Mississippi River and settling in downstate Quincy, according to the Archdiocese of Chicago. Tolton graduated from Quincy University, but because no American seminary would enroll a Black student, he went to Rome to study for the priesthood, according to the archdiocese.

After Tolton was ordained in 1886, he conducted his first Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica and Rome and was sent back to Quincy as a missionary. He started his ministry in Chicago in 1889, leading the all-Black parish St. Monica’s Catholic Church at 36th and Dearborn.

Tolton died at Mercy Hospital from a heart attack at in 1897. He was 43.

Cardinal Francis George announced the cause for canonization for sainthood for Tolton in 2010. Pope Francis signed a decree in 2019 moving the process forward and deeming Tolton “venerable.”

A STEAM school named for him — Tolton Catholic Academy — is in Chatham.

Earl Wiley Renfroe

Credit: Photo courtesy UIC College of Dentistry.

Credit: Photo courtesy UIC College of Dentistry.Considered one of the “fathers of orthodontics.” Earl Wiley Renfroe was the first Black man to head a department at the University of Illinois Chicago College of Dentistry.

Born in 1907, Renfroe went to Austin O. Sexton Grammar School in Woodlawn and then Bowen High School. He was the only Black student in his class at both schools, according to the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics.

Renfroe went to Crane Junior College and onto UIC, putting himself through college by working at the Post Office. He ranked first in his class when he graduated in 1931 and received his license to practice general dentistry the following year, according to the journal.

Renfroe helped end the segregated practice of only allowing dental students to practice on patients of the same race. In 1942, he received his master’s in orthodontics from UIC, making him the first Black dentist in Chicago, and perhaps the United States, to become an orthodontist, according to the journal.

After the Pearl Harbor attacks, Renfroe volunteered for the Army Air Corps. He’d previously received his pilot’s license, making him one of the first Black people in the country to do so, but he could not receive clearance for flight duty in World War II because of age limits. He eventually was stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, and served as chief of the dental service.

Renfroe opened a practice in The Loop after returning to Chicago from the war and resumed teaching at UIC. When he was appointed chair of UIC’s orthodontics department in 1966, he was the first to obtain such a rank at UIC and in the country, according to the journal.

The World War II veteran lent his expertise to other countries, writing textbooks while teaching in Brazil and Barbados, the latter naming a dental facility after him, according to the journal. UIC’s School of Dentistry honored him with a distinguished alumnus award in 1988.

When Renfroe died in 2000 at 93, he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Listen to “It’s All Good: A Block Club Chicago Podcast” here:

Credit: Source link